Last updated: 20 October 2023

By Maynard Paton

I have developed my investing approach after 25-plus years of learning about the stock market and experiencing what actually works for me.

Significant influences on how I invest include the strategies of Warren Buffett, Peter Lynch and Jim Slater. I read the following books during the early 1990s and would still recommend them today to anyone starting with the stock market:

These days I attempt to invest in respectable companies run by capable managers that trade at modest valuations — and to hold the shares for the long term. You could call the strategy RAMP investing: Respectability at a Modest Price (I have talked about my investing approach on these podcasts).

But years ago I would seek only ‘quality’ businesses that enjoyed what Warren Buffett described as competitive ‘moats’.

Over time I deviated from that approach because companies with truly sustainable competitive advantages — at least in the UK — are very rare and often highly rated.

Instead I started evaluating companies where the competitive advantage was due mostly to the people in charge.

These companies were typically small but offered very respectable (but not truly spectacular) financial economics, enjoyed reasonable prospects and — most importantly of all — employed management that cared about the long-term returns for all shareholders.

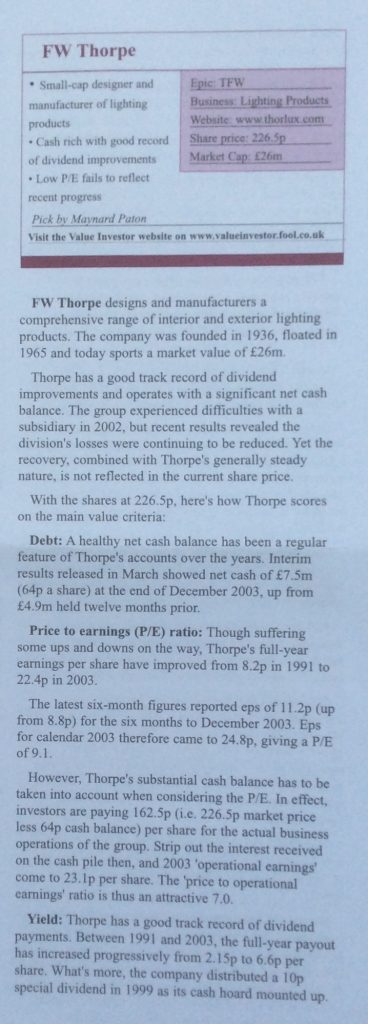

A textbook example is FW Thorpe. The introduction to my BUY report summarises my approach well:

“It’s funny how the dullest companies can produce some of the very best returns for patient investors.

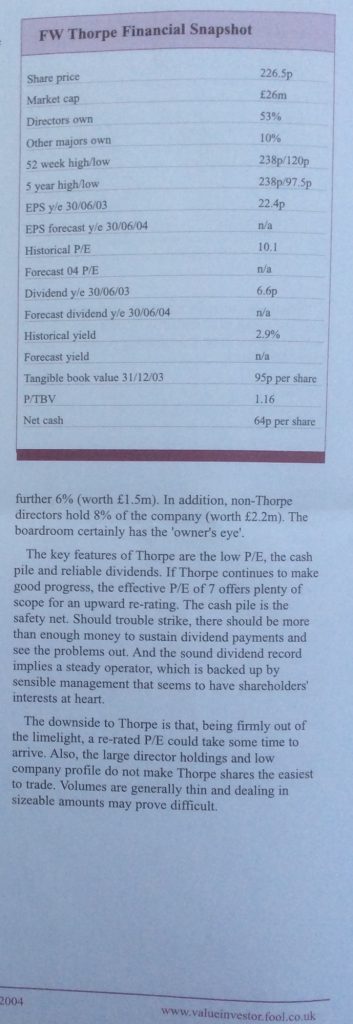

Take FW Thorpe (TFW) for example. I wrote about this obscure lighting business for my former employer back in 2004, when the market cap was £26m and the share price was 23p (adjusted for a later 10-for-1 split).

Today, TFW’s market cap is £156m and the price is 135p — a 500% return if you include dividends collected along the way.

Read my write-up from 2004 below (apologies for the poor-quality images) and you’ll discover family management running an ordinary business that was blessed with plenty of spare cash and liked to pay a rising dividend with the occasional special payout.

Fast forward 11 years and you will see in my write-up today that there is still family management running an ordinary business… that’s still blessed with plenty of spare cash… and still likes to pay a rising dividend with the occasional special payout!”

It just goes to show that successful companies do not always have to boast fantastic patents, powerful brands or some other form of Buffett-type ‘moat’.

Instead, companies run by dedicated executives with a proven, long-term mindset — and have a sizeable financial commitment riding on the share price — can also make the difference.”

Though I do tweak my philosophy from time to time, my stock-picking approach has five core foundations.

Admittedly some points are more clear-cut than others, so occasionally a lot of subjectivity, experience and instinct comes into play. Nevertheless, I believe keeping to a checklist can help me deliver reasonable returns and become a more informed investor.

Contents

Checklist

1. Management

This is an area I believe most investors do not pay enough attention to.

Great companies in my view are in fact the by-product of somebody in charge putting the firm’s people, profits and products to very good use. Employee culture — which is dictated by the board — can make huge differences to share-price returns.

Take for example Daejan and Mountview Estates. Why did these property groups emerge from the banking crash unscathed when many other companies in the sector teetered on the brink?

Both Daejan and Mountview were blessed with conservative management that cared about long-term returns because the directors owned substantial shareholdings themselves… and so the companies never borrowed significant amounts just in case the worst ever happened.

I therefore want my investments to be led by loyal and capable bosses who have served in the top job for several years. I want to see improvements to earnings and dividends throughout their leadership. Better still is the founder/entrepreneur boss, who set up the company in the first place, has led it ever since and has therefore shown even more commitment to building the business and creating shareholder wealth.

I also feel executive remuneration — especially the more generous packages — can tell you more about the board’s priorities than any chairman’s statement. I am keen to avoid ‘fat cats’ and ‘salarymen/women’, and instead prefer to track down leaders that have more investor-friendly pay arrangements.

In particular, I like to see the chief exec’s wages grow no faster than the dividend. I also like to see him/her collect a meaningful dividend income, own sensible option grants and receive appropriate bonuses.

(How To Evaluate Company Management has further details)

2. Accounts

Somebody once said accounting is the language of business and it’s the numbers — not the chairman’s statement — that often tells me whether a business is really good or bad. This is what I look for in the figures:

a. Clarity: Complex accounts equal a complex business and are much more likely to harbour nasty surprises. Standard no-go areas for me include banks and those funny Lloyds insurers, and I avoid anything where the bookkeeping is not clear.

b. Low/no borrowings: I do not want companies that are dependent on the kindness of bank managers. I always ensure my investments have manageable borrowings or, ideally, no debt whatsoever.

c. Low/no pension issues: I see final-salary schemes as potential timebombs. Nobody really knows the exact level of future contributions they require and I prefer to back companies without any pension obligations whatsoever. (How To Evaluate Pension Deficits has further details).

d. Solid cash flow: Businesses must generate cash to survive and the very best ones generally drown in the stuff. I want to see my investments report profits backed up by cash flow, with manageable amounts diverted into working capital and capital expenditure.

e. Respectable margins: I’m attracted to businesses with good margins, say 15% or more, as they suggest some sort of competitive advantage that encourages customers to pay that little bit extra. Companies with enduring competitive advantages can often produce more predictable earnings, which can mean more predictable returns.

3. History

I always obtain as many old annual reports as possible before investing. I want to know how the company has progressed over time and what has caused any past upsets.

If the business has lifted profits every year for decades, then I am much more likely to invest. I am less likely to invest if the last downturn caused huge losses and required a major rescue. That said, I am prepared to overlook haphazard track records if other factors on my checklist are extremely appealing. One example is Tristel, where I overlooked a clumsy history and the share became a ten-bagger.

4. Prospects

I feel investment success can be hard to achieve in sectors that have unfavourable (or somewhat uncertain) long-term prospects. I am especially keen to avoid ‘value traps’ — lowly-rated shares where the underlying business is destined to go the way of textiles and typewriters.

I am quite happy to back mature companies whose growth prospects may be pedestrian, as well as firms whose immediate prospects are dimmed only by wider economic problems. I do not demand my shares operate in ‘growth’ sectors. While it would be nice to have an industry tailwind to support an investment, it can be difficult to pinpoint future winners in new dynamic industries.

5. Valuation

I only want to buy undervalued businesses for my portfolio and I prefer to base my sums on simple measures such as the price to earnings (P/E) ratio, dividend yield and price to book. In my experience, the more complicated the valuation measure, the greater chance of errors and the ‘undervaluation’ not actually existing.

I do not look at cash flow multiples, as earnings over time should be supported by cash flow. If earnings have not been supported by cash flow, I would have doubts about the company’s reporting and I would be unlikely to invest anyway.

I don’t want to pay too much for current-year earnings. The lower the multiple paid, the greater scope for a share-price re-rating if future profits can grow at a respectable rate. Lower multiples should also help limit the downside if future profits go into reverse.

I like a good dividend income, ideally something in excess of the market’s own yield, to bolster my total returns.

For some investments, a share price backed mostly by items on the balance sheet — especially cash, investments and freehold property — will suffice if earnings and dividends appear temporarily depressed.

Find your own edge

But that’s how I invest. You should develop your own way of investing to suit your own experience, knowledge and personality. What (sort of) works for me may not work for you.

While we can all can read about ace investors such as Warren Buffett, we can’t exactly replicate what they do. The situation is a bit like learning to play tennis and using Roger Federer as the starting point. Best to accept that you might not be the next Buffett/Federer, lower your initial expectations and learn the basics first.

My advice is to take only broad themes from the market gurus and try to adapt them into your own style. That’s what I have done using those three aforementioned books.

I have learned that returns can be hampered by imitating gurus too closely. A prime example: for decades Warren Buffett famously did not invest in technology companies because he claimed not to understand their competitive advantages.

Many Buffettologists therefore missed out on the superb gains from Amazon, Google, and so on, because they were too wedded to the great man’s approach. Instead they may have bought into local newspapers, which Buffett once loved but have since proven to be difficult investments.

Over time you will find opportunities that attract you but are dismissed by gurus and experts. If your research is right and you have the courage of your conviction to invest — and you then earn a great return — your confidence as an investor will grow. The gurus can then be pushed to one side as you develop your winning style further.

Your investing approach should be repeatable over time — that is, out-performance should be expected in both bull and bear markets. Many investors do well in the good times, only to find out they were ‘bull-market geniuses’ when markets suddenly turn. Bear markets have a habit of unraveling strategies that possess no real substance.

Investing is a competitive activity and you need to find an edge to succeed. Edges come in different forms. Here are four to consider:

1. Industry ‘scuttlebutt’

You may have worked in a particular industry and know:

- How the sector operates and the factors that can lead to higher profits;

- What industry changes are afoot and the effect they may have on supply and demand, and (perhaps most importantly);

- Why industry customers choose to work with some companies but not others.

In contrast, most pro investors know only about investing, spend a lot of time with spreadsheets and rarely have any first-hand experience in the sectors in which they invest. Your industry experience may give you the upper hand to determine the sector winners from the also-rans.

Discovering what makes a company attractive to customers will set you apart from many investors. The aforementioned Peter Lynch used the term ‘scuttlebutt’ to describe the process of on-the-ground research. Being a customer yourself will help enormously. Reading up on trade publications can help your investigation, as can online resources such as company social-media accounts and review sites for gauging customer feedback.

Having the necessary scuttlebutt in place when markets tumble may help prevent you from panic selling at the bottom — and may even encourage you to buy. When you have developed a conviction about a company, its products and why the customers buy, you are more likely to have a conviction about the stock during unpredictable times.

2. Speaking to management

Part of any scuttlebutt ought to involve speaking to management — or at least listening to management during presentations.

Websites such as PI World and InvestorMeetCompany offer free access to company webinars, and the associated Q&A opportunities are great opportunities to probe directors with awkward questions. AGMs of course provide even greater opportunities — and with smaller companies you may have the floor to yourself.

But management conversations can be double-edged swords. Directors are typically optimistic and can spin a great growth story when the reality may be quite different. They may also supply snippets of information that sound positive but ultimately have little meaningful impact on the wider business . You may misinterpret ‘body language’, too.

My golden rule when attending company presentations is ‘be prepared’. Do your homework first, draw up a list of useful questions and do not rely on others to quiz the directors on your behalf (most attendees don’t ask questions).

During every Q&A, typically somebody asks “What is your USP?” — the answer to which the directors have reeled off numerous times with a very convincing answer. Same with Brexit. Do not ask standard questions.

If nothing else, ask about customers. Who are they? Why do they sign up? Why do they leave? Why do they not sign up? Why do they go to competitor X?

3. Reading reports and RNSs

Many private investors depend on secondary sources of information such as broker notes and investment magazines. Such material is designed to be easy to read and supposedly prepared by an expert to help you make an investment decision.

But you will never become a really good investor relying on secondary sources — not least because other investors will read the same note or magazine and will of course act on the same information.

To get ahead of the crowd, you must read primary sources of information such as results RNSs and annual reports. That way you cut out the middleman ‘expert’ and always have the full facts to hand. Broker notes and investment articles are based mostly on information lifted from company documents anyway. Read a handful of RNSs every morning and you will soon become a more informed investor.

Few investors read annual reports because the documents are seen as too long and too boring. And yet they are often full of ‘outsider’ information that can explain the potential and products of a business through case studies and other material.

Get used to reading annual reports, and you will unearth all sorts of informative small-print — not least director pay — that’s overlooked by everybody else. I routinely study the annual reports of my holdings to find information omitted from the results RNS.

4. Understanding accounting

Most amateur investors know little about accounting while the City pros never have time to study the books closely.

Out of 100 random shareholders, I guess ten may read the accounting footnotes and perhaps one may study the footnotes very closely.

Join those ten out of 100, and you will enjoy an advantage. Become that one in a 100, and you have every chance of spotting something untoward that much of the City will realise only after it’s too late. Obscure But Important Annual-Report Small-Print provides some ideas of where to look.

You do not have to become a qualified accountant to become a successful investor. But a good understanding of the accounting basics is required and any strange term you find in the books can always be looked up online.

The gold-standard accounting book I learned from was Interpreting Company Reports and Accounts by Holmes, Sugden and Gee, but the last edition was published in 2008.

Phil Oakley’s How To Pick Quality Shares and Keith Ashworth-Lord’s Invest In The Best offer good primers for evaluating accounts in listed companies, while Tim Steer’s The Signs Were There is a recommended read to learn about bookkeeping ‘red flags’.

For complete accounting novices, blog reader Derek Stone tells me his Understand Accounting book is ideal. Derek’s Youtube channel is also worth watching.

Some of my ShareScope (formerly SharePad) articles have highlighted particular accounting topics:

- Revenue recognition: Manolete Partners

- Capitalisation of intangible assets: Craneware and Accesso Technology

- Adverse working capital and poor cash conversion: Mears

- Extended intangible useful lives: Frontier Developments

- Profit adjustments: Imperial Brands

- Pension deficits: Norcros

- Acquisitions: LoopUp

- Various unusual disclosures and auditor resignation: Cake Box

Always compare companies to others in the sector. The accounts of Patisserie Holdings showed no obvious signs of fraudulently activity, but a comparison with similar operators raised questions that (with hindsight) ought to have been pursued.

5. The emotional edge

The edges above relate to intellect and effort — reading and interpreting information.

But you can develop a fifth investing edge, based on emotion. Not becoming too excited during frothy markets and not becoming too despondent during market crashes is emotionally very difficult for many stock-pickers.

If you can control the urge to follow the crowd in to and out of shares, then you could perhaps outperform the large swathe of investors who can’t resist the market’s siren calls. No great genius nor specialist expertise is needed with this edge, and it works just as well with trackers and funds as it does with individual equities.

Other useful tips

More investing advice I have found very useful:

1. The ABC of investing

Sometimes investing is similar to forensic police work. Through industry ‘scuttlebutt’, speaking to management, reading reports and understanding accounting, you look for clues to tell you exactly what is going on — and what the wider market may have missed.

The clues could point to potentially good news or bad. But you will not find them if you do not look — and nobody will do this work for you.

Here is a quote from a crime scene manager extracted from the Guardian:

“The anticipation kicks in as soon as I get the call. I get in the car, put on some classical music and start thinking. Every crime scene is different. It’s nowhere near what you expect.

When I arrive, I get a briefing from whoever’s at the scene. You listen but you don’t necessarily agree. I call it ABC. Assume nothing. Believe nobody. Check everything.”

Adapt this ABC to your portfolio research and you will become a better investor through independent thinking. No longer will you be influenced by half-baked opinions from commentators who have not done their homework.

2. The Loser’s Game

Written by Charles Ellis during the 1970s, this seven-page essay transformed my approach to investing after reading it during 2001.

The gist: if you can accept you do not have the talents of Warren Buffett, you stand a good chance of beating all those investors who think they do have his talent (but in reality do not).

A parallel is drawn with amateur tennis: “The way to avoid mistakes is to be conservative and keep the ball in play, letting the other fellow have plenty of room in which to blunder his way to defeat.”

My favourite quote:

“Simplicity, concentration and economy of time and effort have been the distinguishing feature of the great players’ methods, while others lost their way to glory by wandering in a maze of details.”

More good advice:

“Know your policies very well and play according to them all the time.”

“Try to do a few things unusually well.”

“Almost all of the really big trouble that you’re going to experience in the next year is in your portfolio right now.”

Maynard Paton

Hi Maynard,

Thanks for the wonderful write-up. I have recently started reading your articles and find them very enriching and insightful.

I am fairly new to equity investing and find it difficult to crunch accounts from an investing perspective, there are many online resources however I was looking something far more reliable and handy. Is there some book/resource you would recommend.

Thanks and regards

Jay B

Hi Jay B

Thanks for the comment and I am glad you like the blog.

The early general investing books that helped me were: The Zulu Principle (and Beyond the Zulu Principle) by Jim Slater, One Up On Wall Street by Peter Lynch and The Warren Buffett Way by Robert Hagstrom.

Crunching numbers — I read this book back in the day: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Interpreting-Company-Reports-Geoffrey-Holmes/dp/0273711415 Not been updated since 2008 though.

Others to consider are:

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Invest-Best-principles-long-term-investing/dp/0857194844/

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Signs-Were-There-investors-company/dp/1788160819

I have not read this one, but people say it is good:

https://www.amazon.co.uk/How-Pick-Quality-Shares-Three-Step/dp/0857195344/

Maynard

This blog of ‘How I Invest’ should be required reading for any small investor starting out in the stock market. Having invested in equities for the last 15 years my performance would have benefited greatly from following the tips outlined above. Writing down the reasons for and against an investment is an excellent discipline, and helps any review of an investment which has failed to live up to its potential. It also helps temper the short-term enthusiasm to buy a stock which is so easy to do on internet trading platforms. Attending AGMs can also be useful as long as you have done your homework on the company and are not going just for the lunch. Monitoring the daily RNS announcements on websites, such as Investegate, is worthwhile. Apart from results announcements, pay attention to announcements of changes in directors share stakes. I am not interested when directors exercise nil-cost share options which I heartily dislike, but am interested when they invest sizeable chunks of their own money (a rule of thumb is £50,000 say) in a company. The same goes for share sales. I like firms where management retain a sizeable stake, although the presence of a big family ownership is not always a sign that the family will make good long-term stewards. (Daniel Thwaites, my local brewer in Blackburn, is a textbook example of where an old family has presided over the long-term decline of a once valuable company). Finally, I like to watch which institutions are on a company’s share register, and follow movements in their share holdings. Whilst professional investors have better access to company managements than private investors, the latter has one big advantage over them. A small investor can trade in and out of small cap shares much more easily than a big investor with a 5% stake to shift. The presence on a company’s share register of well regarded small cap investors such as Hargreave Hale(now part of Canaccord Genuity), Schroders, Lion Trust, Aberforth, Artemis, etc, can give some reassurance, although not too much weight should be placed on them. Finally, I would heartily recommend Maynard’s suggestion to take advantage of the rapid growth in company webinars to learn about a company and its management. Thanks Maynard for some excellent advice.

Hi Bill,

I am glad you liked the post and many thanks for making some great points. I am planning to add more to the post in time!

but am interested when they invest sizeable chunks of their own money (a rule of thumb is £50,000 say) in a company. The same goes for share sales. I like firms where management retain a sizeable stake, although the presence of a big family ownership is not always a sign that the family will make good long-term stewards. (Daniel Thwaites, my local brewer in Blackburn, is a textbook example of where an old family has presided over the long-term decline of a once valuable company).

Yes, significant director buys catch my eye as well. Not a buy signal on their own perhaps, but alongside other favourable factors they do help to cement the decision to invest. Agreed on the family ownership point. ‘Fiefdom’ risk must always be considered and evidence of the family delivering for shareholders is a must before investing — otherwise you could become stuck in what are very often illiquid shares.

Maynard

Hi Maynard,

Looking at your more than commendable average annual return of, c.13.6%, how is the effort worth the candle when the S&P 500 averaged 14.2% over a similar 12 year period.

I would be interested to know your view on why invest in a portfolio of companies than index i.e.’buy the market’ (a la Bogle)?

It’s understood this is a fascinating hobby. I am unsure however if stock investing is something amateurs should undertake because it is fiendishly difficult, not least due to the investment psychological self-harm which will probably be (unknowingly) undertaken.

Thanks,

Ben

Hi Ben

Vast majority of people should buy the market as per Bogle. Mad stock-pickers such as me are addicted to the game and believe there’s always a multi-bagger just around the corner. I have been absorbed by the stock market for too long to do anything about it now.

Maynard

Hi Maynard,

Reviewing my half-loss in Bioventix and whether it is a top-up or sell for me lead me down a rabbit hole to here. I am quite fearful of the China-first policy and threat to their business – I mean, for example, which African nation would not want Chinese testing for half the price of Bioventix? Any thought’s on this as of the 1000 business sectors out there, the Chinese are killing it – everything from caviar to garlic to humanoid robots. And then at the other end the American’s AI startups have the other half of service-based-sectors covered. Like you, I’m a UK small-cap only investor so really puzzled what to do as I’m sitting on paper losses despite 1,000’s hours of efforts (I note your above last Q&A). Any thoughts for us to evolve rather than becoming extinct, and I mean as small-cap UK investors rather than UK Plc.

Also I am fearful for your portfolio, (Bioventix aside), where you had 30% in System1 in March and the share-price has since more than halved – did you have any guardrail’s setup?

Stay positive – that’s why I try to listen to a lot of Nick Train that the turnaround is very near and even if 1% of the Mag7 AI sell-off by Brit’s ends up in UK smallcaps the AIM market could double!

Hi Nas

Thanks for the message.

Yes, China is a real threat to many businesses and BVXP is one of them. I would like to think BVXP’s Alzheimer’s R&D will eventually come good and counterbalance the loss of Chinese revenue. But that may be wishful thinking. I attended the BVXP AGM the other week and the chief exec claimed BVXP “will still have a business in China in 2030“, although the accompanying explanation was quite vague. A plausible investment approach would be just to assume all of BVXP’s Chinese revenue disappears and then work out how profit would then look, and then judge that projected profit versus the share price.

All we can do as UK small-cap investors is assess whether China-first and AI could have any impact on the profits of each of our holdings. I look at some of my shares, such as ASY, SUS, WINK and MTVW, and think probably no. But I look at TFW, MCON, SYS1, BVXP and possibly CLIG and think probably yes.

I did not have any ‘guardrails’ with SYS1. Quite the opposite in fact. You may wish to read this to understand the 30% position.

I would be careful about Nick T and any other fund manager sounding positive when their performance has been awful. Their messaging must be bullish because they wish to persuade their remaining clients to stay loyal and not join the exodus to the S&P 500 (or now even the FTSE 100). Mind you, at some point Nick T and co will be right — but will us UK small-cap punters live long enough to enjoy our day in the sun?

I am currently preparing my end-of-year round-up blog posts, which will outline the portfolio damage from SYS1 and BVXP. Stay tuned!

Maynard