Note: This Blog post has been extracted from my Q2 2017 Portfolio Update and my Q3 2017 Portfolio Update. The studies were performed during 2017 and, although the basis of my analysis has not changed, my verdicts have not been updated for subsequent events.)

14 January 2019

By Maynard Paton

This Blog post outlines how I evaluate company management and uses my share portfolio for examples.

As I have stated in How I Invest (my bold):

“I want my investments to be led by loyal and capable bosses that have served in the top job for several years. I want to see improvements to profits and the dividend throughout their leadership. Better still is the founder/entrepreneur boss, who set up the firm in the first place, has led it ever since and has therefore shown even more commitment to building the business.”

For the first part of the study I assess management loyalty and commitment (through a sizeable ordinary shareholding). I then look at management capability and track records.

Contents

- Textbook management tenure and shareholdings

- ‘Salarymen’ executives

- ‘Moats’ versus ‘Knights’

- Management that offered the tenure but not the talent

- Management capability and track records

- The A-rated all-stars

- The B-rated bosses

- One C, two Ds, an E and two N/As

- Conclusion

Textbook management tenure and shareholdings

I have ranked my 16 holdings into three groups based on tenure and shareholdings.

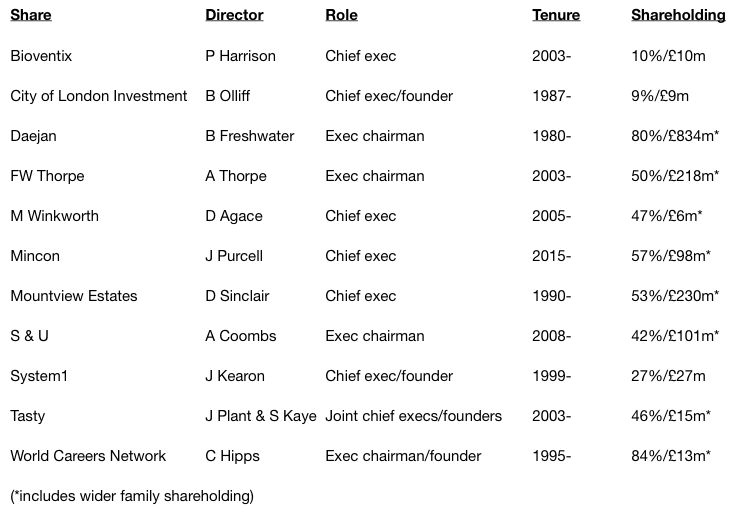

Here is group A:

These are the companies where the lead executive has generally been in charge for a long time and has a substantial amount of money riding on the share price.

You may have spotted that Mincon chief exec Joseph Purcell has the shortest tenure as a boss at just two years.

However, he did serve as chief technical officer from 1998 while his father (currently a Mincon non-exec) was in charge between 1977 and 2012. As such, Mr Purcell ought to have a good understanding of how to run the business.

Otherwise, I would say those eleven shares appear to be textbook holdings for me — at least on a management loyalty and commitment basis.

‘Salarymen’ executives

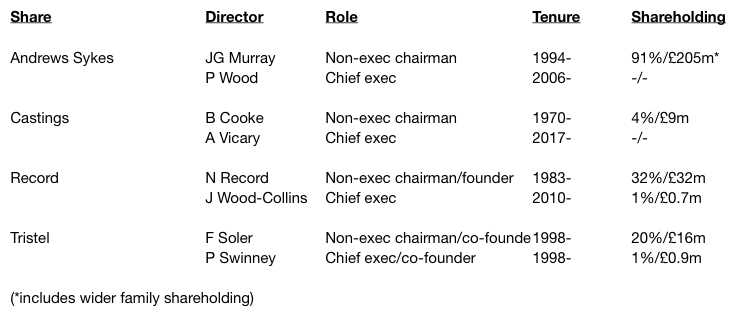

Now to group B:

These are the four holdings where the chief exec does not offer a long tenure or a significant shareholding (or both).

However, what (I hope) saves the day is the presence of a non-exec chairman that boasts either:

- a long executive history (e.g. Castings), or;

- a significant shareholding (e.g. Andrews Sykes and Tristel), or;

- both a long executive history and significant shareholding (e.g. Record).

I would like to think these chairmen would look to protect their investments (and mine) by appointing a fresh chief exec should the need ever arise.

So far at least, none of these ‘salarymen’ chief execs has let me down too badly.

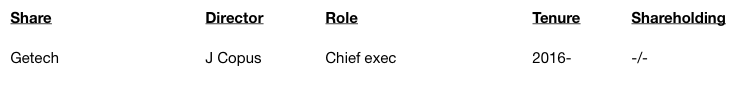

Finally there is group C… consisting of just Getech:

There is no getting away from this… various board changes have left a new chief exec — who owns no shares — running the show.

Not even a major shareholder sits on the board, either. Getech’s founder still holds 10% but he left the company a few years ago.

‘Moats’ versus ‘Knights’

Years ago I used to believe that traditional business ‘moats’ — such as brands, patents, regulations, economies of scale, network effects, and so on — were the most critical feature of any investment .

But these days, such ‘barriers to entry’ appear increasingly at risk of being challenged by intrepid startups that can use the Internet to gain customers much more quickly than ever before.

This investment paper cites a good example of Gillette and Dollar Shave Club.

Over time then, I have become far more convinced about the importance of management ‘knight’s to an investment.

Put simply, I would like to think a business is more likely to enjoy long-term success — and fend off intrepid startups from crossing the ‘moat’ — with a loyal and committed executive at the helm.

(Indeed, a company’s positive and adaptive working culture — instigated by a loyal and committed boss — can in itself be a difficult-to-replicate advantage.)

On the other hand, I am no longer so sure about professional ‘salarymen’ executives, who may be quite happy to run things in a customary way and risk becoming complacent when it comes to fresh competition.

Management that offered the tenure but not the talent

Of course, investing in a business that’s led by a long-time executive with a major shareholding is no guarantee of stock-market success.

Looking through my past investments, I recall Electronic Data Processing, French Connection, Instore and London Capital all offered ‘owner-orientated’ directors…

…but that did not prevent those shares losing me money or struggling for years to deliver a gain.

What counts is backing loyal, committed — and capable — bosses. I sadly discovered the leaders at Electronic Data Processing, French Connection, and so on, were not that capable…

Management capability and track records

The next part of my analysis was not at all straightforward.

I mean, exactly how do you assess management capability and track records… and arrive at a fair and proper judgement?

Do you concentrate on profit growth? What about return on capital? Is dividend consistency considered? Or does share-price performance outweigh everything?

To be honest, I was not entirely sure how to accurately measure the leadership talent at my 16 shares.

In the end, I chose to judge the bosses on length of tenure mixed in with overall operating profit growth, dividend consistency and the frequency of ‘setback’ years — times when profit fell significantly (more than 20%) and/or when the payout was cut.

I have assessed each leader since they took on the top job (limited to the last 20 years), or since their company floated, whichever is the shorter period.

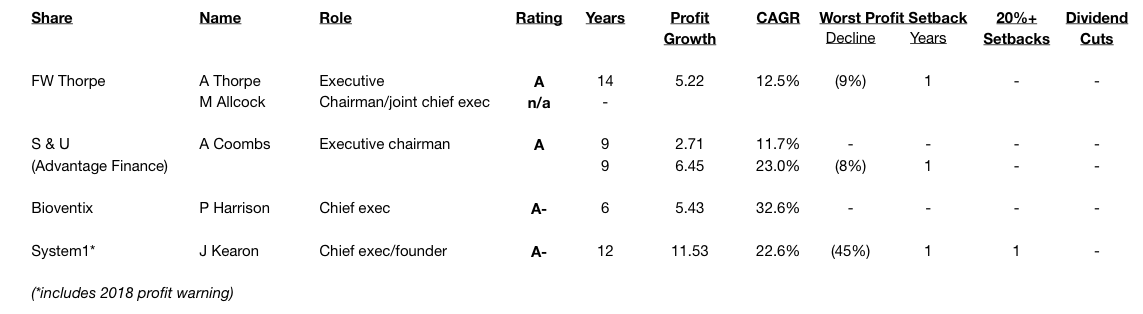

The A-rated all-stars

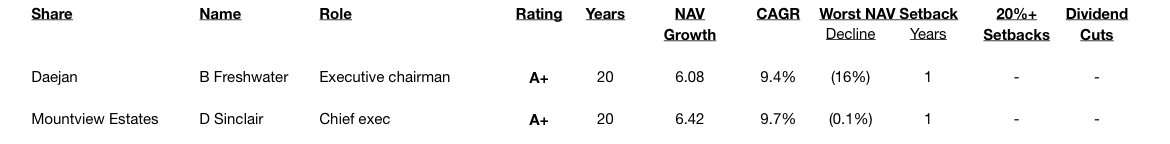

Let’s begin with the two A+ all-stars of this part of the study.

Being property companies, Daejan and Mountview were assessed on their net asset value (NAV) growth rather than profit growth:

Benzion Freshwater and Duncan Sinclair have been in charge of their respective companies for 25-plus years.

During the last 20 years, they’ve advanced their NAVs by more than 6-fold, which equates to compound annual growth rates of about 9%. Such long-time progress without any major setbacks gave these two bosses top marks.

Next up are another four directors who I rate very highly:

For FW Thorpe, I’ve assessed long-time leader Andrew Thorpe, as he remains an executive (albeit part-time). I’m hoping some of Mr Thorpe’s ‘A’ rating will rub off on Mike Allcock, who is Mr Thorpe’s newly appointed successor and has been a prominent director since 2003.

S&U is not the easiest firm to evaluate, given it sold one of its two divisions the other year. I have therefore assessed Anthony Coombs mostly on the performance of the remaining Advantage Finance operation, which has grown very quickly since he became executive chairman during 2008.

For Peter Harrison at Bioventix, I think a few more years of good progress without setbacks and he will join the ‘A+’ club.

Even though System1 has recently issued a 2018 profit warning, the group will still have advanced operating profit at 20% per annum since John Kearon floated the firm during 2006. I think that longer-term achievement deserves an ‘A-’ grade.

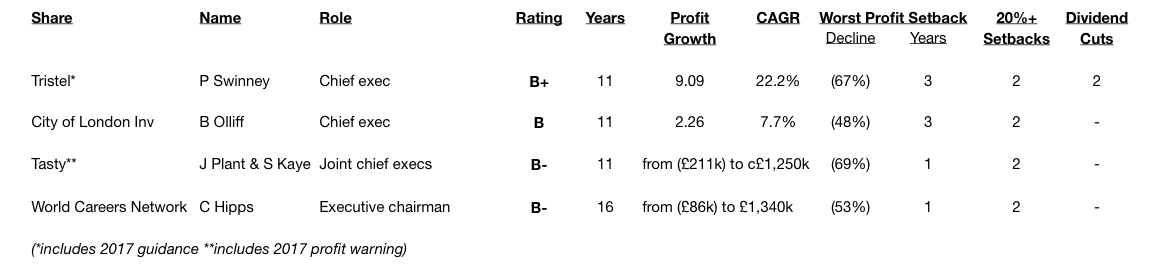

The B-rated bosses

This next group consists of four bosses that, for one reason or another, just did not make the top tier:

I could not award an ‘A’ grade to Paul Swinney of Tristel because three years of his tenure witnessed a 67% profit slump and two dividend cuts. However, that grade may well become an ‘A’ if Mr Swinney extends the overall 20% growth rate he has already overseen.

I must admit Barry Olliff at City of London Investment was not the easiest to assess. Long-time profit growth of 8% a year has been acceptable, but progress has been far from smooth. Still, I think Mr Olliff’s 11-year stewardship deserves some merit.

My ‘B’ verdicts for Jonny Plant and Sam Kaye at Tasty, and Charles Hipps at World Careers Network (now renamed Oleeo (OLEE)), were influenced by both companies having transformed from loss-makers into profit-makers.

I also considered the fact that both of the groups’ earnings have been far higher in the past.

Indeed, I think these company leaders could have managed ‘A’ grades had I performed this review two years ago and before various setback occurred.

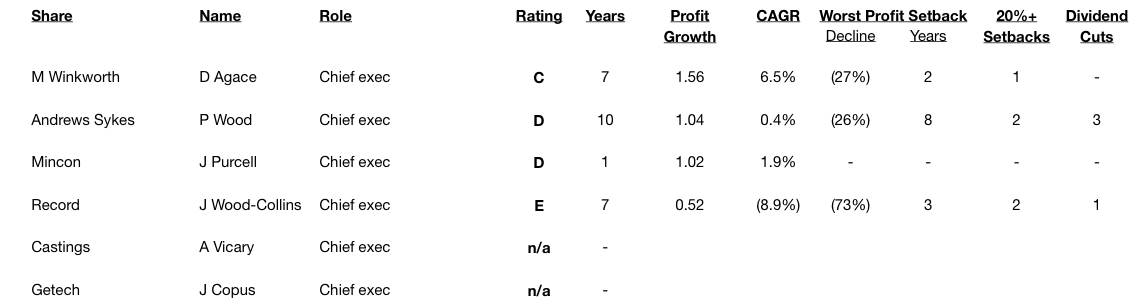

One C, two Ds, an E and two N/As

This fourth group contains the remaining six bosses:

In retrospect, I may have been a little harsh on Dominic Agace of Winkworth. I gave him a ‘C’ because his tenure at the top is not as long as some of the others, while profit at his firm remains quite low at £1.3m. I reckon Mr Agace will enjoy a rating upgrade should earnings advance in due course.

I feel a bit sorry for Paul Woods of Andrews Sykes. He took charge of the hire group during 2006 and had to suffer a few lean years after the banking crash. Furthermore, the company’s 87% owner — and his haphazard demand for dividends — has not helped matters.

Still, running a business for 10 years and watching profit fall by a quarter over 8 years deserves a ‘D’. Recent results, however, do show Andrews Sykes making good progress.

Meanwhile, I awarded Joseph Purcell of Mincon only a ‘D’ because of his short tenure in the top job.

However, it was not difficult to mark James Wood-Collins with an ‘E’. Mr Wood-Collins is the only boss in my review to have stewarded an overall profit downturn during his leadership.

Similar to Andrews Sykes, a bit of bad timing could be involved here. Mr Wood-Collins joined the currency manager in the midst of a client exodus following the banking crash.

Nevertheless, operating profit being reduced by almost 50% over seven years is hardly an executive achievement to boast about.

I sadly could not assess Adam Vicary of Castings and Jonathan Copus of Getech as neither executive has had their first year of leadership captured within any accounts.

Conclusion

This capability and track-record analysis was not a straightforward exercise.

I think my A-grades for the top six bosses are reasonably justified, but plenty of judgement was certainly needed at the ten other shares.

In particular, some ratings were influenced by previous, protracted setbacks that were caused by events outside of management’s control. Other grades were influenced by current setbacks that may only cast a temporary shadow.

No doubt some of you will disagree with a few my verdicts. In fact, you could also ask why I am holding companies with D-, E- or even N/A-grade management.

Well, I suppose it could be a combination of:

- the shares were bought originally when the management ratings were higher;

- the boss perhaps demonstrating talent before taking up the top job;

- other attractions that might offset the lack of an A-rated boss, and/or;

- the company has already suffered difficulties and a new leader could turn things around.

Anyway, the only conclusion I can really make from this study is that my portfolio is not full of proven executive all-stars. I will just have to wait and see whether any of this makes a difference to my future returns.

Maynard Paton

PS: You can receive my blog posts through an occasional email newsletter. Click here for details.

Disclosure: Maynard owns shares in Andrews Sykes, Bioventix, Castings, City of London Investment, Daejan, Getech, Mincon, Mountview Estates, Oleeo, Tasty, FW Thorpe, S&U, System1, Tristel and M Winkworth.

Interesting article. The top executives will be driven to promote the company’s expansion if they have a significant stake in the company’s share ownership. Keep abreast of developments in business, the economy, and the market. This increases your possibility of taking swift action to seize chances or avoid them.