(Note: This blog post was extracted from my Q3 2018 Portfolio Update. An updated version (March 2021) can be found through this SharePad article)

03 January 2019

By Maynard Paton

Today I am continuing to evaluate my shares with some thoughts on company pension deficits. As I have stated in How I Invest:

“c. Low/no pension issues: I view final-salary schemes as potential timebombs. Nobody really knows the exact level of future contributions they require and I prefer to back companies without any ‘employee benefit liabilities’ whatsoever.”

Let me start by saying this blog post is not a definitive analysis of company pensions. Whole books can be written on what is a complex subject, and sadly I am not a company-pension expert.

Nonetheless, judging pension schemes should be important to investors — not least because the schemes can suddenly start absorbing extra cash that might otherwise be paid to shareholders as dividends.

I get the impression many companies trade on lowly ratings because investors worry about the associated pension schemes becoming financial ‘black holes’. You could say these shares are potential ‘value traps’.

Contents

- Defined-contribution vs. Defined-benefit

- Annual reports

- Calculating a pension deficit or surplus

- BT shows what can go wrong

- How to judge whether a pension scheme has a problem

- Comparing pension assets to benefits paid

- Norcros set to pay benefits until 2070

- Christie Group’s deficit looks under control

- Andrews Sykes, Castings, S & U and FW Thorpe

- Summary

Defined-contribution vs. Defined-benefit

Pension schemes fall into two basic categories — defined-contribution and defined-benefit.

Defined-contribution schemes ought to cause no problems for shareholders. Employers (and employees) simply pay into these schemes, and the eventual employee pension then depends on how much was paid in and how well the investments have performed.

Crucially, companies make no promise as to what level of pension will be paid from a defined-contribution scheme.

In contrast, defined-benefit schemes do promise what level of pension will be paid — and so cause all of the headaches for investors.

How much employees receive from their defined-benefit pension is based typically on their salary and length of employment — and may not be commensurate to what was paid in.

As such, defined-benefit schemes can be underfunded if the scheme (in hindsight) promised employees too much… and shareholders can be left to foot the bill.

The annual report will have full details

All companies have to disclose their pension arrangements within their annual reports.

For companies operating only defined-contribution schemes, the disclosure can be as simple as this:

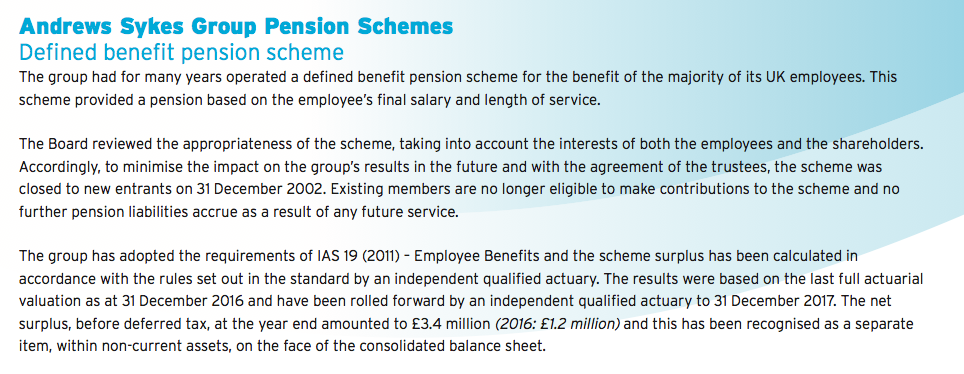

For companies operating defined-benefit schemes, the disclosure will be far more expansive. The annual report should refer to the defined-benefit scheme within the management narrative:

…and there will be a long accounting note detailing the scheme’s funding, movements and calculation assumptions. (Defined-contribution schemes require no such accounting note).

Calculating a pension deficit or surplus

Within the accounting note for a defined-benefit scheme, you will find a summary highlighting the scheme’s assets, liabilities (or obligations) and the resultant surplus or (more likely) deficit.

The summary for Andrews Sykes shows a £3.4m surplus:

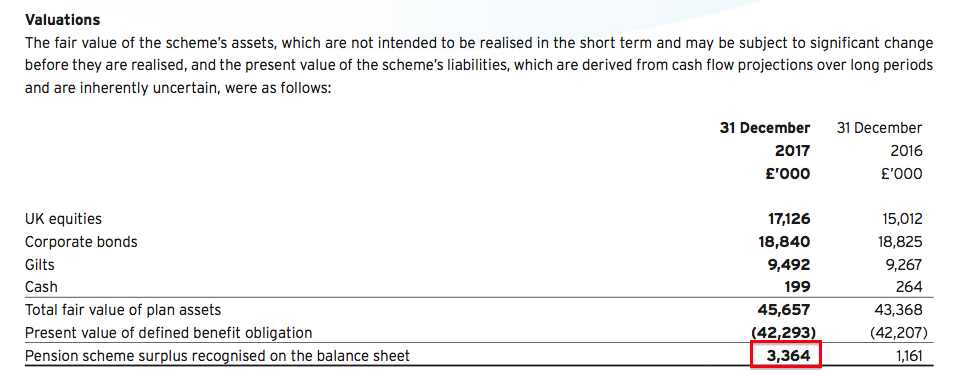

The summary for BT (BT.A) shows a £6,371m deficit:

Understanding scheme assets is simple enough — they reflect the value of the scheme’s various investments at the balance sheet date.

However, scheme liabilities are more convoluted — they reflect the estimated total payments to be made by the pension scheme discounted back to the balance-sheet date.

The liabilities calculation involves all sorts of assumptions about future salaries, inflation, employment tenure and life expectancy — and the assumptions are devised by the board with the help of its advisers.

Unfortunately, a scheme showing a pension surplus is not necessarily ‘funded’ and a scheme showing a deficit is not necessarily ‘underfunded’.

You see, complicating matters further is the fact that the calculated ‘accounting’ liabilities shown in the annual report are not used to determine the level of contributions needed for the scheme.

Instead, a ‘funding’ valuation has to be performed on behalf of the scheme’s trustees every three years, and it is this separate calculation — with the agreement of the company — that sets the necessary contribution level.

BT shows what can go wrong

BT shows what can go wrong with defined-benefit pension promises. BT’s scheme has shown an accounting deficit every year except 2008:

| Year to 31 March | Pension assets (£m) | Pension liabilities (£m) | Pension surplus/(deficit) (£m) |

| 2005 | 29,628 | (34,435) | (4,807) |

| 2006 | 35,640 | (38,187) | (2,547) |

| 2007 | 38,390 | (38,779) | (389) |

| 2008 | 37,448 | (34,669) | 2,779 |

| 2009 | 29,353 | (33,326) | (3,973) |

| 2010 | 35,429 | (49,293) | (7,864) |

| 2011 | 37,222 | (39,052) | (1,830) |

| 2012 | 38,541 | (40,989) | (2,448) |

| 2013 | 41,566 | (47,422) | (5,856) |

| 2014 | 40,113 | (47,135) | (7,022) |

| 2015 | 43,627 | (51,210) | (7,583) |

| 2016 | 43,968 | (50,350) | (6,382) |

| 2017 | 51,112 | (60,200) | (9,088) |

| 2018 | 50,956 | (57,327) | (6,371) |

An announcement in May revealed the group had agreed to pay greater contributions to try and eliminate the deficit.

Essentially BT had been planning to pay £7.6b into the scheme between 2018 and 2030. Now the trustees have asked for £13.2b — an extra £5.6b — of which £2b will be funded by BT taking on extra debt.

BT’s 2018 adjusted operating profit was £4.0b, so paying an additional £400m-plus every year (on average) is significant. For BT shareholders, that £400m is money that could have been distributed as dividends.

Following the revised contribution announcement, it is perhaps no surprise BT’s share price currently trades near a five-year low and the trailing 7%-plus dividend yield hints at a payout cut.

Note, too, that BT’s revised agreement requires the telecom firm to pay even more to the pension scheme if shareholder dividends and/or buybacks reach certain levels. Furthermore, sizeable disposals may also trigger extra scheme payments, while consultation with the trustees is required if significant acquisitions are planned.

I must say, having pension trustees interfering with business decisions can’t be great for BT’s board or investors.

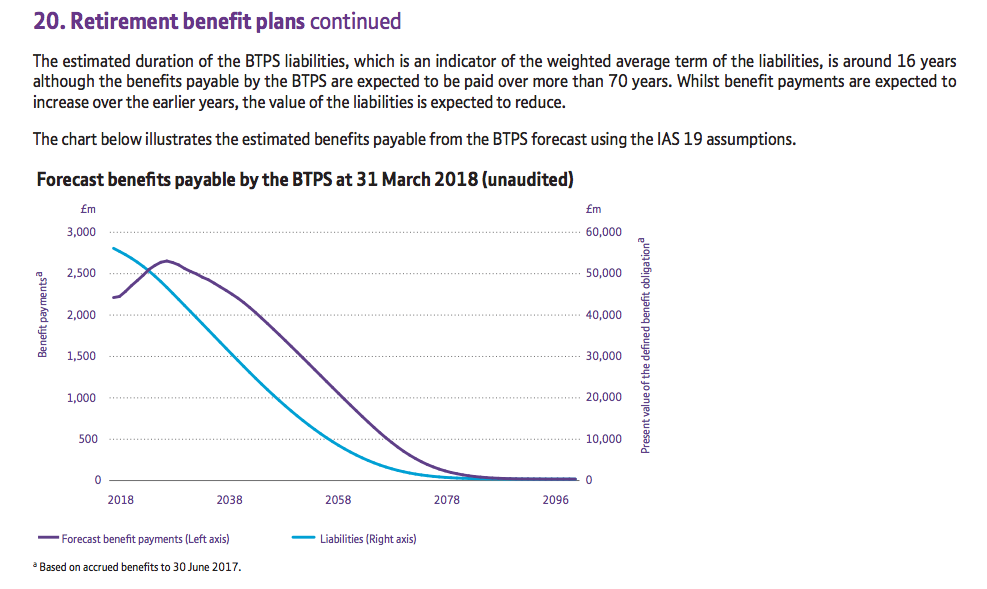

Anyway, here is a sobering chart from BT’s 2018 annual report:

Annual benefits paid to BT’s pensioners are predicted to drop below current levels only from 2038 onwards. Benefits are then expected to be paid until 2090!

How to judge whether a pension scheme has a problem

So how can you judge whether a pension scheme is likely to suffer BT-type problems?

I have to admit… I am not sure you can predict exactly if a scheme will become a financial ‘black hole’.

That said, applying some basic checks could help — and if you are in any doubt, it is probably best to stay out.

One easy rule of thumb is to compare a company’s operating profit to the reported accounting deficit.

Ideally you would want the operating profit to dwarf the deficit — so if problems do hit the pension scheme, the company’s earnings and dividend ought not to come under great threat.

BT’s pension deficit has regularly exceeded the firm’s operating profit:

| Year to 31 March | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| Adjusted operating profit (£m) | 3,421 | 3,655 | 3,828 | 4,135 | 3,991 |

| Pension deficit (£m) | (7,022) | (7,583) | (6,382) | (9,088) | (6,371) |

As such, any adverse pension movements — and knock-on trustee decisions — were always going to risk a notable hit to BT’s finances.

I would not blame you if you avoided any company with a sizeable pension deficit — or even any company that operated a defined-benefit scheme — altogether.

I mean, your portfolio would become completely free of worries about complex actuarial calculations and pension trustees trying to snaffle your dividends!

That said, if you — like me — wish to study pension schemes, you might find the following number-crunching useful.

Comparing pension assets to benefits paid

I look at company pension schemes as I would my own pension pot.

Say I need £20k a year to live on during my old age. How large a pension pot would I need?

Annuity rates (at June 2018) for a 65-year-old are approximately 5.6%, or 4.0% with an annual 3% escalation. For a 55-year-old, the level rate is 4.5% and escalation rate is 2.8%.

I might plump for 4%, which requires a £500k pot to give £20k a year.

Of course, annuity rates are guaranteed while the returns from equities — which many company pension schemes hold — are not.

So if my own pension pot holds shares, I might plump for a rate lower than 4% — which would mean a larger pot to start with and more room for manoeuvre should markets slump. For example, I would need a £667k pot if I assumed I could collect 3% a year.

With those rates in mind, evaluating some of the country’s largest pension schemes becomes quite instructive.

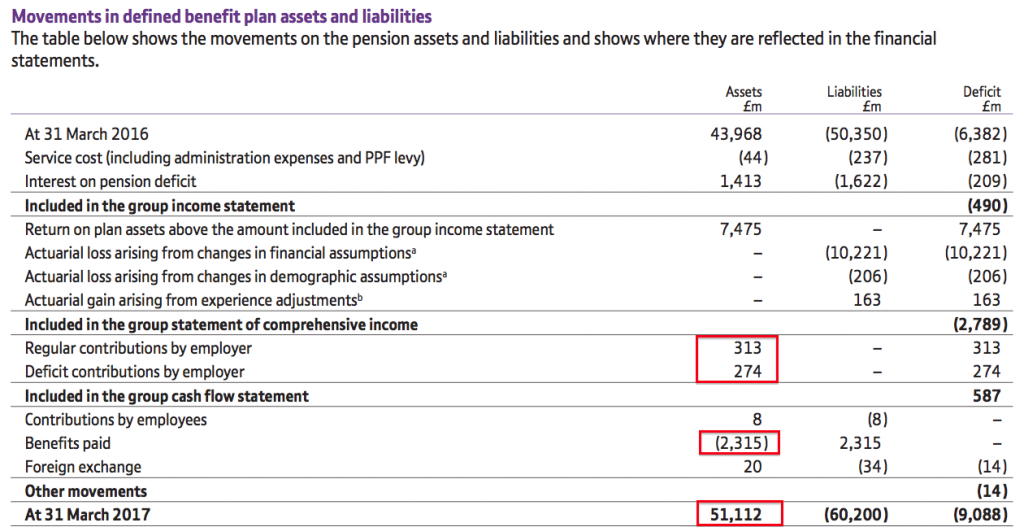

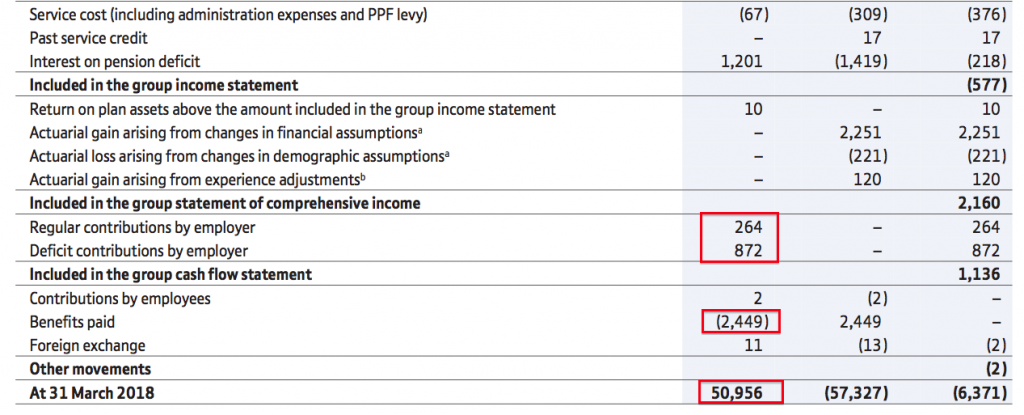

I always compare the benefits a pension scheme pays to its members to i) the assets held by the scheme, and; ii) the contributions the scheme receives.

The benefits a scheme currently pays to its members, the contributions paid into the scheme, as well as the assets a scheme holds, can all be found in the relevant pension accounting note.

I have highlighted the entries for BT below:

The table below lists 15 blue chips and the effective returns their schemes require to pay the current level of pension benefits:

| Company | Year to | Pension assets (£m) | Pensions benefits (£m) | 'Required return' (%) |

| AstraZeneca | 31 Dec 2017 | 9,922* | 581* | 5.9 |

| BAE | 31 Dec 2017 | 26,991 | 1,303 | 4.8 |

| BP | 31 Dec 2017 | 35,091* | 1,903* | 5.4 |

| British American Tobacco | 31 Dec 2017 | 12,350 | 534 | 4.3 |

| BT | 31 Mar 2018 | 50,956 | 2,449 | 4.8 |

| Centrica | 31 Dec 2017 | 8,451 | 287 | 3.4 |

| Diageo | 30 Jun 2017 | 9,226 | 503 | 5.5 |

| GlaxoSmithKline | 31 Dec 2017 | 18,280 | 881 | 4.8 |

| Imperial Brands | 30 Sep 2017 | 4,732 | 251 | 5.3 |

| National Grid | 31 Mar 2018 | 23,858 | 1,285 | 5.4 |

| Royal Dutch Shell | 31 Dec 2017 | 93,243* | 4,294* | 4.6 |

| J Sainsbury | 31 Mar 2018 | 9,884 | 362 | 3.7 |

| Severn Trent | 31 Mar 2018 | 2,340 | 107 | 4.6 |

| Unilever | 31 Dec 2017 | 22,382** | 1,239** | 5.5 |

| Vodafone | 31 Mar 2018 | 6,697** | 289** | 4.3 |

| Average | 4.8 |

(*US dollars, **Euros)

So for BT, paid benefits of £2,449m from assets of £50,956m lead to a ‘required return’ of 4.8% — coincidentally, the average of those 15 blue chips.

Of course, those 15 companies continue to contribute to their schemes, and so the ‘required return’ figure can be adjusted by subtracting the contribution sum from the benefit paid:

| Company | Pension assets (£m) | Pension benefits (£m) | Pension contributions (£m) | Benefits less contributions (£m) | 'Required return' (%) |

| AstraZeneca | 9,922* | 581* | 157* | 424* | 4.3 |

| BAE | 26,991 | 1,303 | 519 | 784 | 2.9 |

| BP | 35,091* | 1,903* | 509* | 1,394* | 4.0 |

| British American Tobacco | 12,350 | 534 | 254 | 280 | 2.3 |

| BT | 50,956 | 2,449 | 1,136 | 1,313 | 2.6 |

| Centrica | 8,451 | 287 | 236 | 51 | 0.6 |

| Diageo | 9,226 | 503 | 220 | 283 | 3.1 |

| GlaxoSmithKline | 18,280 | 881 | 444 | 437 | 2.4 |

| Imperial Brands | 4,732 | 251 | 140 | 111 | 2.3 |

| National Grid | 23,858 | 1,285 | 475 | 810 | 3.4 |

| Royal Dutch Shell | 93,243* | 4,294* | 1804* | 2,490* | 2.7 |

| J Sainsbury | 9,884 | 362 | 130 | 232 | 2.3 |

| Severn Trent | 2,340 | 107 | 35 | 72 | 3.1 |

| Unilever | 22,382** | 1,239** | 1,105** | 134** | 0.6 |

| Vodafone | 6,697** | 289** | 301** | (12)** | (0.2) |

| Average | 2.6 |

(*US dollars, **Euros)

So for BT, paid benefits of £2,449m less contributions of £1,136m leaves £1,313m to be generated from assets of £50,956m, or a ‘required return’ of 2.6% — coincidentally, again, the average of those 15 blue chips.

The figures for the other companies vary a little, but the 4.8% and 2.6% averages provide good benchmarks for assessing pension schemes in general.

In particular, I would treat any share with a large deficit and much higher ‘required returns’ with some caution. Here is one example.

Norcros set to pay benefits until 2070

Norcros (NXR) manufactures showers, sinks and tiles, and sports a £178m market cap at 215p (as at June 2018).

The table below summarises its profit and pension-scheme history:

| Year to 31 March | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| Adjusted operating profit (£m) | 16.1 | 17.0 | 21.3 | 23.8 | 27.4 |

| Pension assets (£m) | 383.8 | 397.0 | 365.9 | 404.4 | 399.6 |

| Pension liabilities (£m) | (405.6) | (441.3) | (421.6) | (467.1) | (447.6) |

| Pension deficit (£m) | (21.8) | (44.3) | (55.7) | (62.7) | (48.0) |

Norcros’ deficit has consistently exceeded its annual profit — not a great sign.

Now look at the level of benefits being paid versus the assets held by the scheme and the contributions being made:

| Year to 31 March | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| Pension assets (£m) | 383.8 | 397.0 | 365.9 | 404.4 | 399.6 |

| Pension benefits (£m) | 23.6 | 23.1 | 24.1 | 24.2 | 24.0 |

| Pension contributions (£m) | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| 'Required return' (without contributions) (%) | 6.1 | 5.8 | 6.6 | 6.0 | 6.0 |

| 'Required return' (with contributions) (%) | 5.6 | 5.3 | 6.0 | 5.4 | 5.4 |

For some years now, the benefits paid from Norcros’ scheme have represented approximately 6% of the scheme’s assets — somewhat higher than the 4.8% average from those 15 blue chips.

Worse still, Norcros’ £2m contributions appear very small.

All told, it is not clear why Norcros’ scheme can hope for 5%-plus annual returns to cover the benefits being paid (without eroding the scheme’s assets), when those 15 blue chips are seeking an average of 2.4%.

I calculate Norcros would have to contribute an extra £10m a year to its scheme before the ‘required returns’ reduce to somewhere close to the average of those 15 blue chips.

Given Norcros’ underlying operating profit was £27m for 2018, finding an extra £10m could be a tall order. Perhaps that is why the shares trade on a trailing P/E of 7.3.

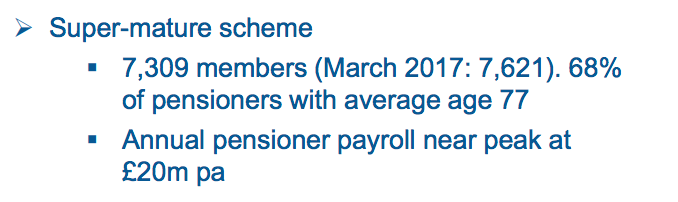

For what it is worth, Norcros claims its scheme is “super mature” with a “pensioner payroll near peak at £20m pa”:

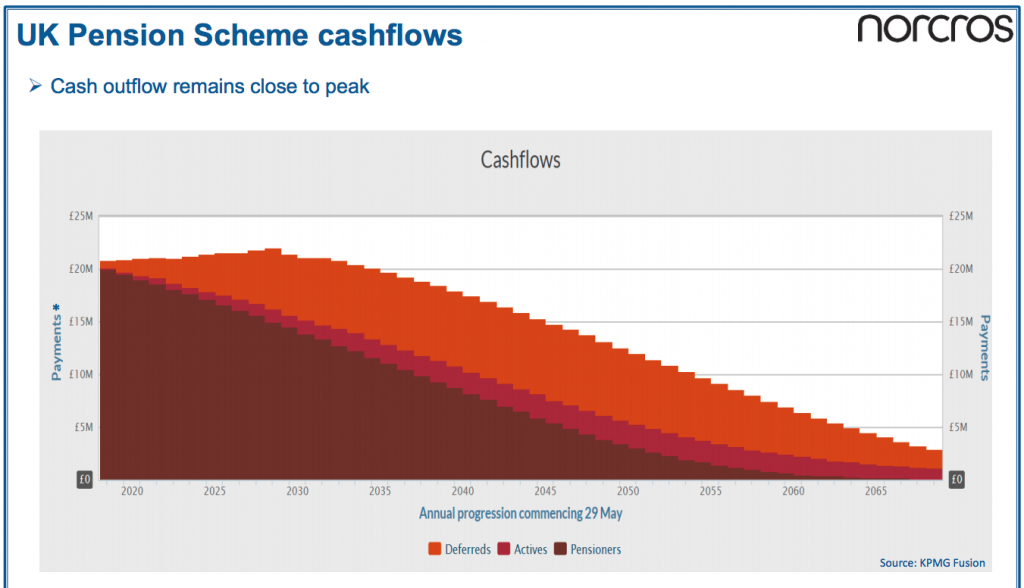

But similar to BT, the projected benefits to be paid to scheme members are sobering:

It seems to me Norcros’ pension scheme will pay benefits at or above the current rate for another 14 years — and continue to distribute benefits until beyond 2070.

If Norcros’ scheme is indeed “super mature”, I would hate to think how far the projections of an immature pension scheme might stretch to.

Christie Group’s deficit looks under control

I should point out that a hefty deficit does not necessarily mean a major funding problem.

Christie (CTG) provides commercial survey, valuation and stock-control services, and carries a £75m market cap at 164p (as at June 2018).

The table below summarises its profit and pension-scheme history:

| Year to 31 December | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

| Adjusted operating profit (£k) | 1,567 | 3,706 | 3,869 | 1,141 | 3,678 |

| Pension assets (£k) | 44,304 | 43,636 | 46,148 | 53,324 | 59,406 |

| Pension liabilities (£k) | (49,100) | (57,606) | (58,106) | (71,430) | (73,647) |

| Pension deficit (£k) | (4,796) | (13,970) | (11,958) | (18,106) | (14,241) |

Similar to Norcros, Christie’s deficit has consistently exceeded its annual profit — not a great sign.

Let’s now look at the level of benefits being paid versus the assets held by the scheme and the contributions being made:

| Year to 31 December | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

| Pension assets (£k) | 44,304 | 43,636 | 46,148 | 53,324 | 59,406 |

| Pension benefits (£k) | 820 | 5,038 | 3,352 | 1,627 | 1,563 |

| Pension contributions (£k) | 1,400 | 1,415 | 1,468 | 1,547 | 1,482 |

| 'Required return' (without contributions) (%) | 1.9 | 11.5 | 7.3 | 3.1 | 2.7 |

| 'Required return' (with contributions) (%) | (1.3) | 8.3 | 4.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

Benefits paid have been up and down, but right now — at £1.6m — scheme assets of £59m should generate most of that every year.

And when you consider £1.5m is injected into the scheme annually as well, Christie’s scheme does look under control — despite what the ‘accounting’ deficit might suggest.

Christie’s trailing P/E of 17 does not indicate the market is concerned about the deficit.

Andrews Sykes, Castings, S & U and FW Thorpe

So if Christie’s large pension deficit can appear under control, can a pension surplus ever hide substantial problems? Potentially, yes — although I have yet to unearth a possible example.

What I can show you instead are the four companies in my portfolio that operate defined-benefit pension schemes. Amazingly enough, all four schemes presently show a pension surplus:

| Andrews Sykes | Castings | S & U | FW Thorpe | |

| Year to | 31 Dec 2017 | 31 Mar 2017 | 31 Jan 2018 | 30 Jun 2017 |

| Pension assets (£k) | 45,657 | 78,263 | 1,151 | 38,424 |

| Pension liabilities (£k) | (42,293) | (61,419) | (533) | (37,710) |

| Pension surplus (£k) | 3,364 | 16,844 | 618 | 714 |

This next table calculates the ‘required returns’ from the associated scheme assets:

| Andrews Sykes | Castings | S & U | FW Thorpe | |

| Year to | 31 Dec 2017 | 31 Mar 2017 | 31 Jan 2018 | 30 Jun 2017 |

| Operating profit (£k) | 17,589 | 15,548 | 32,978 | 18,422 |

| Pension assets (£k) | 45,657 | 78,263 | 1,151 | 38,424 |

| Pension benefits (£k) | 1,687 | 1,768 | 127 | 1,241 |

| Pension contributions (£k) | 920 | - | - | 1,000 |

| 'Required return' (without contributions) (%) | 3.7 | 2.3 | 11.0 | 3.2 |

| 'Required return' (with contributions) (%) | 1.7 | 2.3 | 11.0 | 0.6 |

S & U’s ‘required returns’ do look alarming — but the scheme is absolutely tiny. S & U reported a 2018 operating profit of £33m, which would easily fund the scheme’s £127k benefits should the scheme’s assets ever hit zero.

Castings does not contribute to its scheme, and I would like to think the required 2.3% average return is achievable over time.

Meanwhile, both Andrews Sykes and FW Thorpe still contribute to their respective schemes and, assuming these payments continue, the current level of benefit payments ought not to cause imminent problems.

I should add that the operating profits of Castings, Andrews Sykes and FW Thorpe are at least eight times the size of their respective scheme’s benefit payments. So if the trustees ever did become restless, the effect on earnings may not be too significant.

Summary

As you may have gathered, evaluating company pension schemes is not a straightforward exercise — and I would not blame you for completely avoiding shares that carry sizeable deficits.

I certainly consider pension schemes when looking at companies, and purposely avoid any business where there is a chance of a ‘black hole’ developing.

As BT has demonstrated, pension deficits never seem to go away… and trustees can suddenly demand greater contributions to the potential detriment of your dividend.

Oh, and if you think rising interest rates can eliminate pension deficits and the associated long-term funding problems… don’t forget those charts projecting pension benefits still being paid beyond 2070!

Maynard Paton

PS: You can receive my blog posts through an occasional email newsletter. Click here for details.

Disclosure: Maynard owns shares in Andrews Sykes, Castings, S & U and FW Thorpe.

very useful pitched at realistic level I have tended to only take a superficial look at deficit vs profits

Must sharpen up my act