08 February 2017

By Maynard Paton

Today I’m continuing my hunt for possible investments by revisiting Shoe Zone (SHOE). I first placed this company on my Watch List during March 2015.

Here are the attractions that prompted this revisit:

* Owner-aligned boardroom: The executive family management boasts a 50%/£90m shareholding

* Generous dividend payments: The group will soon have distributed all of its earnings as ordinary and special dividends for the last two years

* Straightforward accounts: The books showcase net cash, modest capex and high returns on equity

As usual, I’m applying a question-and-answer template to help me pinpoint companies that match the criteria set out in How I Invest. I’m looking for as many Yes answers as possible.

Activity: Discount shoe retailer with 500-plus UK/Ireland stores

Website: www.shoezoneplc.com

Share price: 180p

Shares in issue: 50,000,000

Market capitalisation: £90m

Does the business boast a respectable track record?

Not really.

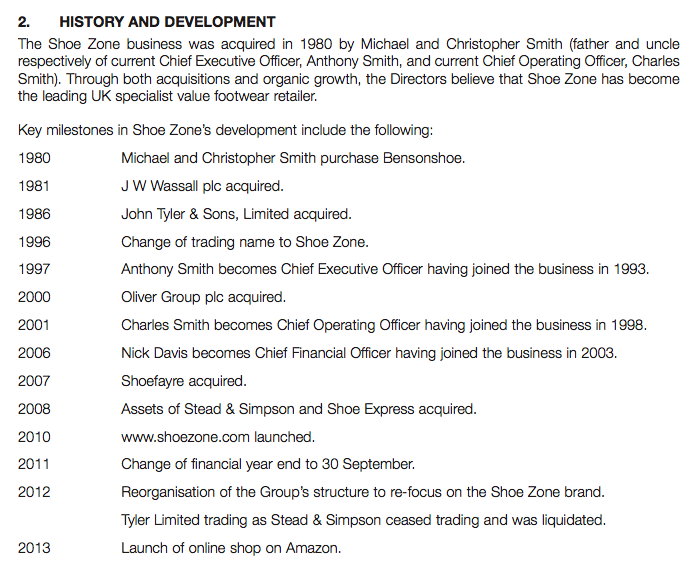

SHOE was effectively established when Michael and Christopher Smith purchased shoe chain Benson Shoe during 1980. The following decades then witnessed various acquisitions, a name change to Shoe Zone and Michael’s sons Anthony and Charles taking charge.

A potted history of the group is shown below:

SHOE joined AIM during 2014 and the firm’s website carries the admission document while Companies House lists group annual reports from 2006 onwards.

The archives show that revenue was £116m and operating profit was £7m during 2005, with revenue having climbed to £160m and lifted operating profit to £10m by 2016. The average compound rate of expansion during those 11 years was a pedestrian 3% per annum.

SHOE reached a high-water mark during 2009, as acquisitions then took revenue to £246m and operating profit to £15m. Progress thereafter has been somewhat haphazard, as a reorganisation culled more than 100 stores and placed under-performing subsidiaries into liquidation.

The last few years have offered an inconsistent performance, with revenue sliding as shops were closed:

| 52 weeks to | 29 Sep 2012 | 5 Oct 2013* | 4 Oct 2014 | 3 Oct 2015 | 1 Oct 2016 |

| Revenue (£k) | 221,114 | 193,882 | 172,861 | 166,819 | 159,834 |

| Operating profit (£k) | 4,566 | 5,307 | 11,505 | 10,282 | 10,386 |

| Other items (£k) | - | - | (936) | - | - |

| Finance income (£k) | (1,041) | (249) | (70) | (142) | (134) |

| Pre-tax profit (£k) | 3,525 | 5,058 | 10,499 | 10,140 | 10,252 |

| Earnings per share (p) | - | - | 16.1 | 16.2 | 16.9 |

| Dividend per share (p) | - | - | 3.6 | 9.7 | 10.1 |

| Special dividend per share (p) | - | - | - | 6.0 | 8.0 |

(*53 weeks)

The ‘other items’ recorded in the table above relate to the 2014 flotation. At least the mixed track record post-listing has not been clouded further with extra ‘exceptional’ costs.

Has the business grown mostly without acquisition?

Yes — or at least it has since 2007.

The latest balance sheet carries no goodwill and no acquisitions have occurred since the flotation.

Has the business mostly self-funded its growth?

Yes.

The 2016 balance sheet displayed share capital of £3m versus earnings retained by the business of £26m. The group carries no debt.

Does the business possess an asset-strong balance sheet?

Sort of.

SHOE’s 2016 balance sheet carried cash of £15m, debt of zero and freehold property with a £10m book value.

Bear in mind that SHOE’s cash position is flattered by significant trade and other payables — that is, money SHOE owes to suppliers and other creditors. At the last count, such sums came to £28m — versus just £7m effectively owed to SHOE by suppliers and other debtors.

As such, I would not say that SHOE’s £15m cash position is entirely surplus to requirements. I note the 2016 results stated the business now plans to operate with at least £11m in the bank at each year-end.

Elsewhere on the balance sheet, the group’s final-salary pension deficit is an obvious drawback.

A rule-of-thumb I have with pension deficits is to be wary of companies with deficits that are greater than their annual profit. I’m careful of large deficits because they can start to absorb extra cash and leave less money for dividends.

Sadly, SHOE’s funding shortfall has swelled from £5m to £13m during the last two years, and currently looks sizeable when compared to the annual £10m operating profit.

Last year the pension fund paid benefits of £3.4m, received employer contributions of £472k and owned assets of £80m.

Compared to other quoted companies with pension schemes showing deficits, I feel SHOE’s £472k contribution is somewhat light and probably ought to increase. The 2016 results said the group was “in discussions around the ongoing funding with the [pension scheme] trustees”.

When I first reviewed SHOE, I discovered the business was not locked into costly and lengthy shop leases. Happily that situation remains the case:

| 52 weeks to | 29 Sep 2012 | 5 Oct 2013* | 4 Oct 2014 | 3 Oct 2015 | 1 Oct 2016 |

| Property lease expense (£k) | 34,176 | 29,171 | 25,153 | 23,493 | 21,722 |

| Minimum lease payments due: | |||||

| Within one year (£k) | 33,586 | 25,130 | 22,866 | 21,292 | 20,404 |

| Between one and five years (£k) | 97,059 | 70,314 | 59,867 | 47,173 | 42,359 |

| After five years (£k) | 54,927 | 30,258 | 19,516 | 10,492 | 7,071 |

| Total (£k) | 185,572 | 125,702 | 102,249 | 78,957 | 69,834 |

(*53 weeks)

Dividing the total future lease commitment (£70m) by the lease payment for 2016 (£22m) suggests the average lease has only 3.2 years left to run.

Does the business convert profits into free cash?

Yes.

| 52 weeks to | 29 Sep 2012 | 5 Oct 2013* | 4 Oct 2014 | 3 Oct 2015 | 1 Oct 2016 |

| Operating profit (£k) | 4,566 | 5,307 | 11,505 | 10,282 | 10,386 |

| Depreciation (£k) | 8,755 | 6,497 | 4,527 | 3,713 | 3,153 |

| Net capital expenditure (£k) | (541) | (2,495) | (1,305) | (1,599) | (3,195) |

| Working-capital movement (£k) | 2,558 | (3,398) | 2,191 | (2,836) | 458 |

| Net cash (£k) | 4,752 | 4,864 | 9,114 | 14,221 | 15,046 |

(*53 weeks)

For the last five years, the aggregate depreciation charged against earnings has been well ahead of the total cash spent on capital expenditure.

However, the 2016 results did say capex would increase by £1m for 2017 to help pay for new stores, refit existing branches and improve the head office.

Meanwhile, working-capital movements since 2012 have added up to produce only a £1m outflow of cash.

Overall, SHOE’s cash generation has been impressive enough to have pushed net cash from £5m to £15m between 2012 and 2016 — and that is after the business paid cash dividends of £19m during the same time.

Does the business enjoy a competitive advantage?

I am not sure.

The flotation prospectus lists the large store network, the Shoe Zone brand, the extensive product range and the in-house logistics as elements of the group’s strengths.

However, as I wrote two years ago, I reckon everything boils down to employing tip-top management — as it always does with retailers. I suppose the board’s long-standing relationships with various Chinese shoe manufacturers may be helpful.

A 6.5% operating margin for 2016 seems impressive for a discount retailer, and suggests the group has developed a welcome, low-cost working culture. That, too, may keep SHOE ahead of its rivals.

Does the business produce a respectable return on equity?

Yes — or at least it has since the flotation.

Return on average equity for 2016 was £8.4m/£33m = 26%, and even adjusting the denominator for the pension deficit still gives a result in excess of 20%.

The percentages for 2014 and 2015 adjusted for the pension deficit both top 20%, too.

A lack of working capital tied up in the business — stock of £30m is counterbalanced almost entirely by the aforementioned £28m of trade creditors — is the main reason for the impressive returns.

Prior to 2014, SHOE’s return on equity was a so-so 12% or less.

Does the business employ capable executives?

That still depends on your view of SHOE’s track record.

The group is led by brothers Anthony and Charles Smith. Anthony was appointed chief executive during 1997 and then executive chairman last year. Charles has been a board executive since 2001.

Anthony Smith is 49 years old and Charles Smith is 51. Backed by their major shareholdings (see below), both men could be spear-heading this business for some time to come.

SHOE’s other executive was appointed as finance director in 2006 and became chief executive in 2016.

Does the business employ good-value-for-money executives?

I think so.

Last year Anthony Smith collected a £250k basic salary while brother Charles collected £200k. Those pay packets do not look outrageous to me for running a £10m-profit business.

Neither Smith has received any pension payment nor any bonus since the flotation — suggesting some restraint pay-wise.

Does the business employ owner-orientated executives?

Yes.

The Smiths sold 45% of the business at the flotation and a further 5% during 2015. They presently retain a combined 50% stake with a current £45m market value.

Special dividends declared for 2015 (6p per share) and 2016 (8p per share) support the notion the executives are behaving sensibly with the group’s surplus cash.

I like the fact SHOE’s ordinary and special dividend for 2016 will mean the Smith brothers will enjoy an aggregate dividend payment of £4.5m — a sum well ahead of their combined basic pay.

I also love the absence of an option scheme.

Does the business enjoy reasonable growth prospects?

Probably not.

Issued last month, the 2016 annual results said:

“Shoe Zone has made a solid start to the year and trading is in line with expectations. We are making good progress against our strategic objectives and the board remains positive about the outlook for the Group for the remainder of the year.”

The strategic objectives mostly involve re-jigging, re-fitting and re-locating the current network of shops. Essentially smaller premises are being swapped for larger units in the hope of generating greater sales. There are 510 outlets at present and the group claims “approximately 500” is the right number for standard Shoe Zone branches.

The only expansion of sorts is a trial of larger ‘big box’ stores, which will all operate with “a new contemporary format, offering a good brand mix, extended product range and broad customer appeal.”

However, just three ‘big box’ outlets are open at present and only another six are planned for 2017.

Anyway, what is quite worrying with SHOE’s store rejuvenations to date is that revenue per outlet has actually been shrinking. Here are my sums:

| 52 weeks to | 4 Oct 2014 | 3 Oct 2015 | 1 Oct 2016 |

| Revenue (£k) | 172,861 | 166,819 | 159,834 |

| Less online revenue (£k) | (3,976) | (5,505) | (6,234) |

| Store revenue (£k) | 168,885 | 161,314 | 153,600 |

| Average store count | 557.5 | 540 | 522.5 |

| Store revenue/average store count (£) | 302,933 | 298,730 | 293,972 |

(*53 weeks)

I would have thought revenue per average store would be rising.

So it seems to me SHOE’s non-renovated stores are now performing very badly, or the group’s renovated stores are not showing much of an improvement. Or perhaps it’s a mixture of the two.

Either way, this revenue-per-store trend suggests to me there could be inherent trading issues at the chain. The shop refits and relocations have been happening for some years now and I am starting to wonder if SHOE is in fact a shrinking business.

Does the share price stand a good chance of becoming a bargain?

The share price may already be cheap.

The 2016 results showed earnings of 17p per share, which place the 180p share price on a multiple of 10.6.

I am not surprised near-term profit growth is predicted to be limited. Broker forecasts signal earnings being maintained around — or just above — the 17p per share level for 2017 and 2018.

Meanwhile, the trailing 10.1p per share ordinary dividend supplies a 5.6% income. Include the 8p per share special dividend, though, and the yield tops 10%.

However, I would not bank on a repeat of an 8p per share special dividend for 2017.

For one thing, the aforementioned £1m increase to capital expenditure will cost an extra 2p per share of cash flow. There may be a possibility of greater pension contributions, too.

Is it worth watching Shoe Zone?

I am not sure.

As before, the real attraction here is the long-standing family managers.

They presumably know the sector inside out and look to be the owner-orientated types with £45m still riding on the share price. I particularly like how they are distributing surplus cash as special dividends and can manage the business without an option scheme.

But I did say two years ago that I was surprised the veteran bosses allowed themselves to reach a point where 100-plus under-performing shops had to be closed.

And now I wonder whether revenue is also shrinking because SHOE is losing ground to rivals.

Simply put, I just don’t understand why revenue per store is declining despite all the branch refits and relocations. I have noted SHOE’s annual reports do not disclose like-for-like sales and I think I understand why.

All that has left me pondering whether SHOE’s shares are a value trap.

True, the dividend alongside any special payouts could yield 6%-plus. But underlying revenue appears to be retreating every year… and it’s difficult to imagine a notable improvement occurring anytime soon.

All told, then, I think there are companies out there with more favourable revenue and earnings prospects, and in turn more favourable share-price prospects.

Excuse the pun, but unfortunately I feel I now have to give SHOE the boot from my Watch List.

Maynard Paton

Disclosure: Maynard does not own shares in Shoe Zone.

Shoe Zone (SHOE)

Additional pension comments:

I thought I’d post a few more remarks on SHOE’s pension deficit and why the company could have to increase its contributions to the scheme.

Back in October I posted on another website about Norcros (NXR) and its pension deficit.

Here is the post:

http://www.stockopedia.com/content/small-cap-value-report-28-oct-2016-entu-156217/?comment=20#20

I wrote:

—————————————————————————————————————–

I reckon the remarkably low PER is because the overpayments are far too modest, and more needs to be pumped into NXR’s scheme.

Rather than speculate about a pension scheme’s future liabilities and what assumptions underpin their calculations, another way of evaluating a scheme is to simply take the plan’s assets and compare them with: i) the contributions made by the employer and employees; and ii) the annual benefits paid to the scheme’s members.

Shareholders can then assess whether the assets and contributions look sufficient enough to produce the required benefits every year.

It’s a bit like assessing your own retirement plans…i.e. I have X in my pot, I need Y to live on every year, and so I need Z% a year from my pot to make ends meet.

For NXR, its pension scheme had year-end assets of GBP 365.9m, while contributions were £2.1m and benefits paid were £24.1m.

So you could say the plan needs 6.6% a year to cover its benefits payments without contributions (24.1/365.9)… or 6.0% if you factor in the contributions ((24.1-2.1)/365.9).

So, 6% a year — sounds easy enough for us smart stock-pickers :-), although as we all know if the fund has a bad year then the required Z% return soon ratchets higher. Benefit payments from pension funds just can’t be deferred as you can with withdrawals from your own portfolio.

Anyway, how does NXR’s required 6% compare to other quoted companies with pension funds?

I have taken the other 18 names from the list Ramridge provided above, to arrive at some idea of relative funding from a decent mix of companies. Here are the required returns in descending order (the negative figure for TSCO is due to its contributions exceeding the scheme benefits paid):

RNO – 7.0%

NXR – 6.0%

CAR – 5.2%

CFYN – 4.5%

DVO – 4.3%

GKN – 3.4%

TATE – 2.8%

BT – 2.7%

GNC – 2.1%

MNZS – 1.6%

MGAM – 1.4%

MACF – 1.3%

BAE – 1.2%

WTB – 1.1%

MCB – 1.1%

SYNT – 0.8%

BRAM – 0.2%

TCG – 0.0%

TSCO – (3.1%)

From this small study, I would say NXR’s contributions are far too modest and more needs to be pumped into the scheme on an annual basis. It is notable perhaps that of the top three, RNO does not pay dividends at present and CAR recently suspended its dividend due to pension accounting technicalities.

I calculate NXR’s contributions would have to rise from £2.1m to £9.5m a year to lower the required plan return down to 4% (assuming benefits stay at £24m a year) and come closer to matching the funding efforts of this sample.

—————————————————————————————————————–

For SHOE the required return figure is (£3,440k – £472k)/£79,704k = 3.7%… and towards the top end of the above sample.

Maynard

Interesting alternative approach to pensions, although it can only be seen as a rough rule of thumb of course. For example Shoezone’s benefits paid in 2016 rose 38% compared to 2015, and 2015’s benefits paid were actually lower (by 3%) than benefits paid in 2014.

Presumably this is due to a range of factors such as the ageing profile of the members, mortality, inflation etc. etc. but given how both the numerator and denominator of your calculation will jump around from year to year I wonder how useful this approach can be in practice.

Another approach I sometimes use does focus on the assumptions underpinning the pension liabilities, specifically the discount rate. Interest rates do not directly affect future payments to pensioners and in my view it is way too prudent of the accounting and actuarial standards to require the use of a discount rate based on gilts or AA-rated corporate bonds when the pension scheme will generally be invested in assets which will return far more than gilts or bonds.

As a (rarely used) alternative, existing actuarial legislation allows for a discount rate based on the expected return of the assets in which the pension scheme is actually invested. e.g. if the scheme is fully invested in equities, you could use a discount rate of say 7%. If they are invested in a mix of equities, bonds, property etc. then make an assumption of returns for each asset class and calculate a blended discount rate based on the asset mix. The sensitivity tables in the pensions note of the accounts then allows one to convert this new discount rate into a revised pensions liability and deficit figure.

Taking this approach with the Norcos scheme, I reckon their pension deficit is in the region of £31m rather than the reported £55.7m, simply by applying a discount rate which (in my opinion) is more appropriate than that used by their actuaries and accountants.

In the context of a £31m deficit, annual deficit reduction payments of £2.5m + inflation seem far more manageable. (Note the deficit payments rose in April 2016 from the £2.1m figure quoted in your Stockopedia post)

This approach is also slightly ‘finger in the air’, but it has the same benefit as your method of only using figures in the published accounts.

Hello bestace

Thanks for the Comment.

“Interesting alternative approach to pensions, although it can only be seen as a rough rule of thumb of course. For example Shoezone’s benefits paid in 2016 rose 38% compared to 2015, and 2015’s benefits paid were actually lower (by 3%) than benefits paid in 2014.

Presumably this is due to a range of factors such as the ageing profile of the members, mortality, inflation etc. etc. but given how both the numerator and denominator of your calculation will jump around from year to year I wonder how useful this approach can be in practice.”

Agreed, and I think any evaluation of pension schemes can only be rules of thumb — or at least for non-experts such as me. The numerator and denominator may move around, but the general trend for both is up (unless the scheme is very mature). What I found interesting is not the result for any individual company, but the overall results for the sample. That gave an indication of why some companies with large accounting deficits may sport stubbornly lowly P/Es — because their scheme contributions looked low compared to those of other companies.

Taking this approach with the Norcos scheme, I reckon their pension deficit is in the region of £31m rather than the reported £55.7m, simply by applying a discount rate which (in my opinion) is more appropriate than that used by their actuaries and accountants.

In the context of a £31m deficit, annual deficit reduction payments of £2.5m + inflation seem far more manageable. (Note the deficit payments rose in April 2016 from the £2.1m figure quoted in your Stockopedia post)

Yes, but even if the deficit was stated at £31m, NXR’s scheme is still on the hook to pay benefits of £24m from assets of £366m.

The following chart from NXR’s interim presentation suggests benefits will be running at £20m-plus until 2030 or so — which is a long time away:

I am not truly convinced NXR’s scheme could endure its asset-value shrinking for a prolonged period or in a sizeable way without needing to increase the company’s contributions. The payments just look low to me based on the amounts many other companies — which all face the same retirement issues as NXR — are injecting into their schemes.

Maynard

I am more confident of Norcros’ propsects. Granted that opinion is a contrarian one and they are certainly in a worse situation compared to other companies, but being worse off relatively does not necessarily mean they are in a poor position on an absolute basis.

Since 2010 the value of assets in the Norcros pension scheme have been reasonably stable, increasing from £355m in 2010 to £366m last year despite annual benefits payments of around £22.5m and annual admin costs of around £1.5m over that period. They have been able to do this thanks to investment returns generated by the assets.

That doesn’t strike me as a pension scheme selling down the family silver to pay for today’s lunch.

One could certainly argue that the last 6 years have been a benign investment environment, but pensions are by definition about long term horizons and 6% investment returns (taking your method) over the long term really shouldn’t be a stretch once you further take into account that 6% doesn’t include the increase in the deficit reduction contributions and as a mature scheme they are near to peak benefit payments (as shown by the chart you linked to).

It is also interesting to note that on a ‘best estimates’ basis the scheme actuary calculated the scheme was marginally in surplus at the date of the last triennial valuation, 1 April 2015.

My own cash flow modelling indicates they could get by on 5% or even 4% investment returns.

Hello bestace

Thanks for the reply. I guess this sort of discussion is an example of ‘what makes a market’ :-)

It will be fascinating to see how NXR’s scheme fares.

Maynard

Thanks for the article Maynard,

The problems with SHOE ZONE is down to Fashion, Fashion and Fashion, and (a bit of) pricing to boot.

Looking at SHOE’s website traffic, they attract 500k/month, whereas BOOHOO does 10m/month, despite both businesses having similar revenue.

In this cutthroat sector, SHOE got to reinvest cash towards creating a credible online division that would be profitable.

SHOE could be winding down its business (hence the dividends payout), then people shouldn’t invest in this business until valuation falls below liquidation value (am eying a 50% discount to current share price or 5 times earnings).

Hello Walter

Thanks for the Comment

I feel there is a certain dependency on fashion at SHOE, but I’m guessing a lot of product revenue is from more ‘standard’ footwear (e.g. school shoes, cheap trainers, boots etc).

Agreed, SHOE’s website efforts appear quite poor at <5% of revenue, but I wonder if the demographic SHOE attracts are likely to be online buyers.

I do get the feeling SHOE is being run for dividends rather that growth, and I think any valuation sums have to take that into account. If a business is being wound down, you must be very sure of your sums and the company's progress in its twilight years, as you can be certain its terminal value will be zero.

Maynard