First, a wealth warning.

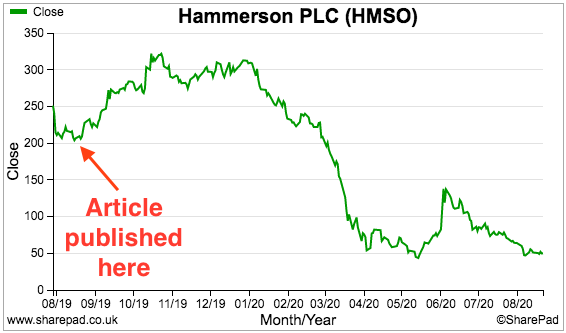

The last price-to-book ‘bargain’ I looked at for SharePad was Hammerson.

Back then the property group’s £5 billion asset base could be acquired for a £1.6 billion market cap. Investors were in theory able to purchase £1 of assets for just 30p.

Twelve months on, and the share price below tells the story:

Sure, Covid-19 has wreaked havoc on the property sector. But Hammerson’s financials were already on rocky ground.

A few choice quotes from that Hammerson article:

- “By far the most shocking headline statistic was net rental income diving 12%.”

- “Hammerson’s cash flow spotlights the precarious financing of the group’s directly owned centres and why properties must now be sold.”

- “Oh dear — Hammerson is selling properties at a chunky 8.5% below their stated book value.”

The pandemic simply amplified existing problems, and prompted the company to launch a deeply discounted rights issue, cull its cash dividend and sell properties for 19% below their book value.

With that in mind…

…brace yourself as I search for another deep-value asset ‘bargain’!

Filter results

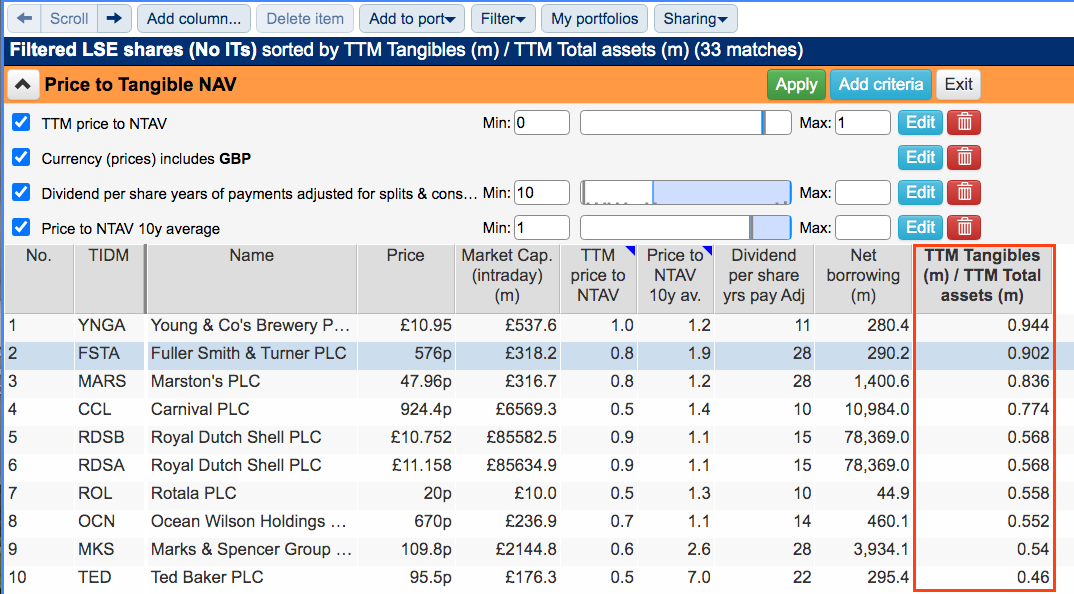

I have tweaked my filtering for this price-to-book screen.

For Hammerson I applied the following criteria:

1) A price to net tangible asset value (‘PNTAV’) of between 0 and 1;

2) A minimum dividend payment history of ten years, and;

3) A forecast dividend yield of zero or more.

This time I have kept 1) and 2) but changed 3).

Instead of the forecast dividend yield, I demanded a ten-year average PNTAV ratio of at least 1.

I made the change in order to exclude ‘value traps’ that always trade below book value.

I also added a fourth criterion to include only shares denominated in GBP.

SharePad returned 33 matches from this revised screen:

(You can run this screen for yourself by selecting the “Maynard Paton 28/08/19: Hammerson” filter within SharePad’s fabulous Filter Library – My instructions show you how. Once selected, click on ‘forecast dividend yield’ criteria, click ‘Edit’ and 1) search for “NTAV” and select “Price to Net tangible asset value (NTAV)” and 2) search for “currency” and select “Currency (prices”, click OK and select “GBP”.)

I included an extra column within the list to help identify the more promising candidates (the red box in the filter results above).

Dividing tangible assets by total assets would direct me to the companies with balance sheets perhaps dominated by property assets rather than items such as stock and debtors.

Wishful thinking perhaps given the events at Hammerson, but property assets should have a more dependable value than, say, stock at a clothes retailer.

A trio of pub groups — Young & Co, Fuller, Smith & Turner and Marston’s — topped my search.

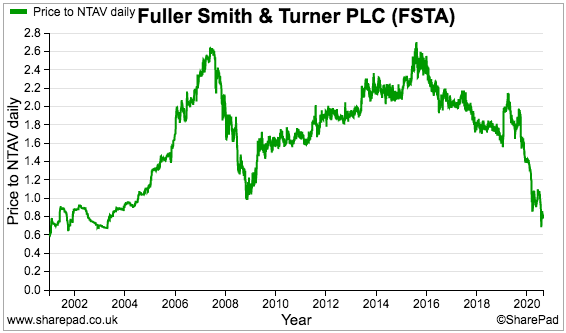

I chose Fuller, Smith & Turner (or ‘Fuller’s’) because its shares over the last ten years had traded at an average 1.9 times net tangible asset value, versus 1.2 times at Young & Co and Marston’s.

I therefore felt the upside potential at Fuller’s could be greater.

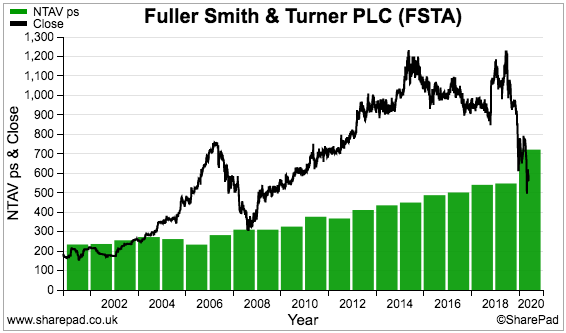

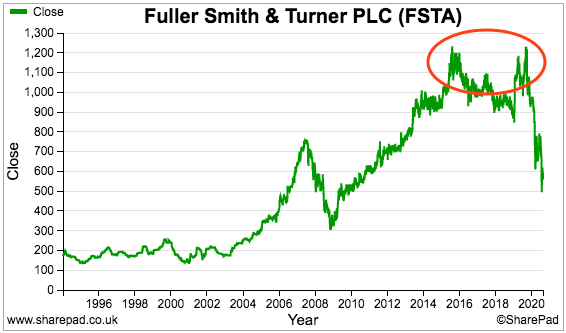

This chart compares Fuller’s share price to its tangible NAV:

Sure enough, only during the early-2000s bear market did the share price previously dip below tangible NAV. Indeed, the shares have often traded at twice tangible NAV:

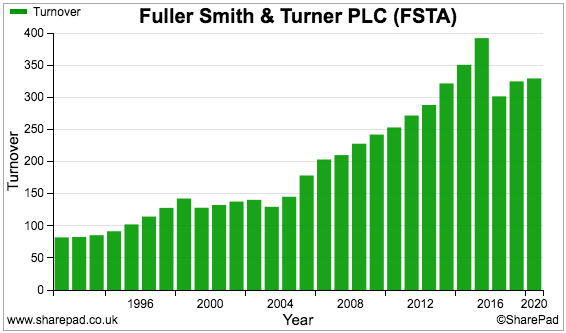

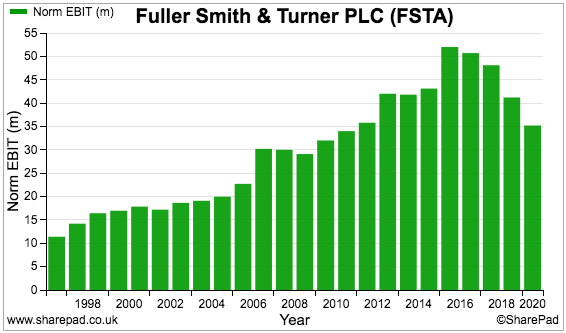

Revenue and profit have generally moved higher over time:

The reductions to revenue and profit during the last few years followed a significant disposal and then the effect of the pandemic.

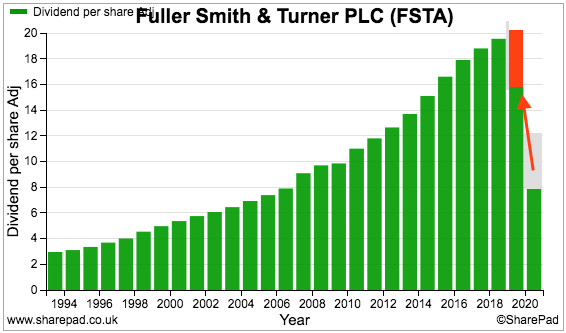

The dividend had shown very predictable progress — until July’s annual results announced the payout had been suspended due to the pandemic:

(Note: I have amended the chart because Fuller’s declared an unusual third dividend for 2019 that has been credited to 2020).

All told, Fuller’s track record suggests a reliable performer before Covid-19 struck. Maybe the business has the wherewithal to recover and trade well above book value once more. Let’s delve a little deeper.

The business of Fuller, Smith & Turner

Those SharePad charts do not do justice to Fuller’s illustrious history. The business was formed during 1845 when John Bird Fuller asked Henry Smith and John Turner to leave a brewery in Romford to work at his brewery in Chiswick:

The complete financial record of Fuller’s since 1845 — or indeed since 1654 when brewing first commenced at the Chiswick site — has sadly long since disappeared.

However, the archives at Companies House do show the business producing sales of £6 million and a £631,000 profit during 1974. Just before Covid-19, sales had expanded to £315 million and profits had advanced to £40 million.

The archives also show the dividend being lifted every year since at least 1974, and never being reduced since at least 1950 — up until 2020 that is.

I am sure the incredible payout history and the presence of long-time family shareholder-management are no coincidence.

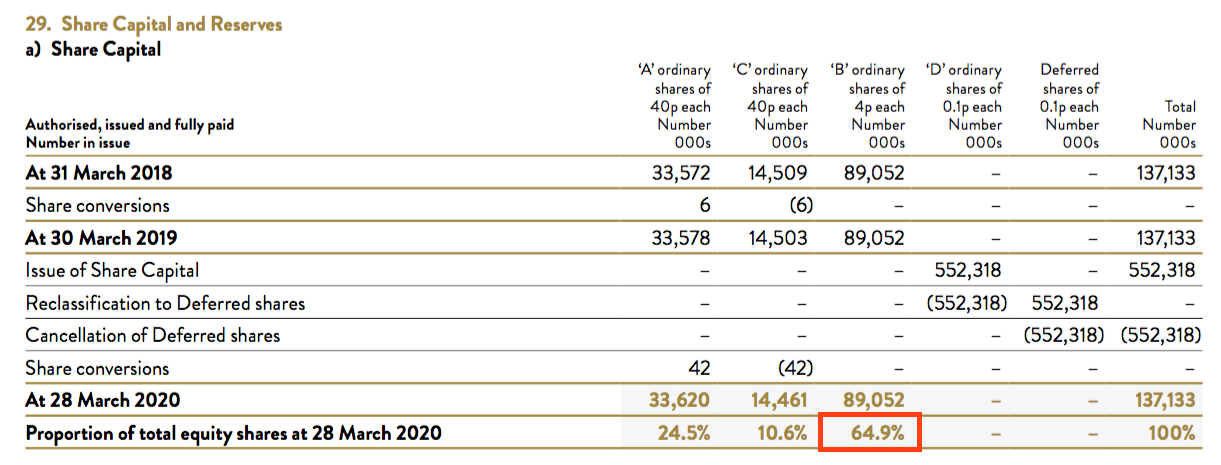

The boardroom currently includes two Fullers and two Turners (but no Smiths), and protecting their interests is an unusual A-B-C share structure.

Fuller’s A shares are the ordinary shares traded on the London stock exchange.

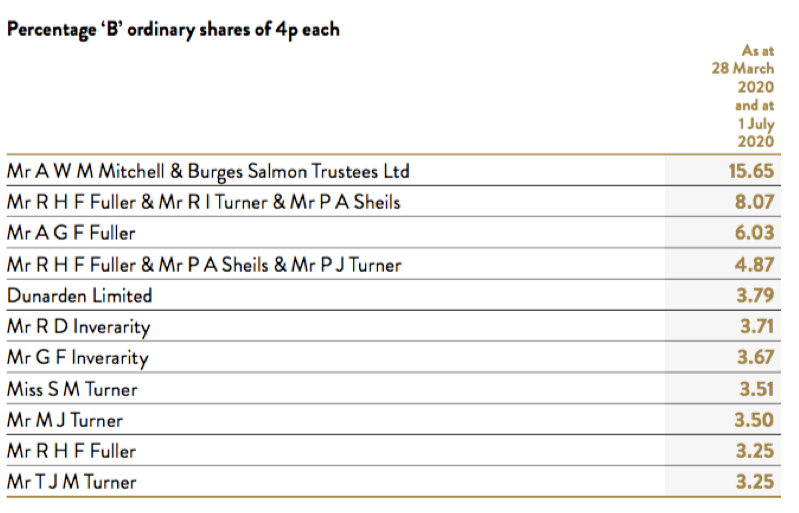

The B shares meanwhile are not listed and can’t convert into A shares. These B shares represent 65% of the share count and appear to be owned mostly by Fuller and Turner family members:

Confusing matters is the fact the B shares collect only 10% of the standard A share dividend.

Confusing matters further are the C shares, which are not listed but can convert into A shares, and do collect the full 100% standard dividend.

The upshot of these B and C shares is that, collectively, the family holders may control up to 75% of the votes and had enjoyed a growing aggregate dividend that reached almost £5m last year.

The Fullers and Turners (and perhaps a few Smiths) may not be too pleased if their sudden loss of income continues for some time.

The dividend suspension was of course prompted by the lockdown. Fuller’s controls almost 400 pubs and hotels mostly in and around London, of which just over half are company-run and the rest let to tenants. The outlets were all shut in March and more than 80% have re-opened since July.

The following text from the 2019 annual report summarised the company’s upmarket positioning:

“Built around iconic sites in stunning locations, often with beautiful bedrooms, we serve delicious, fresh-cooked, seasonal food and an interesting portfolio of premium drinks, with exceptional team members dedicated to providing outstanding customer service.”

Fuller’s was probably best known for brewing London Pride, but the aforementioned Chiswick brewery and associated drink production was sold for £250 million last year. A supply agreement with the brewery’s new owner means London Pride and other beers continue to be served in Fuller’s pubs.

Balance sheet and freeholds

Let’s turn our attention to the all-important balance sheet and book value.

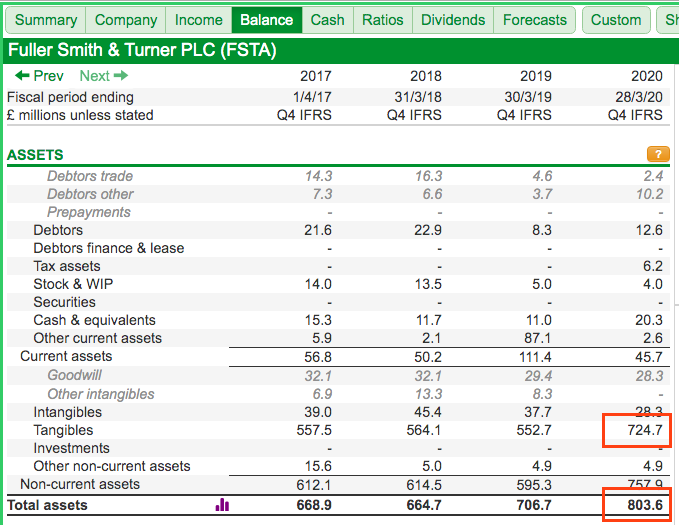

SharePad shows Fuller’s carries assets of £804 million, of which £725 million are tangibles:

We must discover what those tangibles are, which means turning to the annual report.

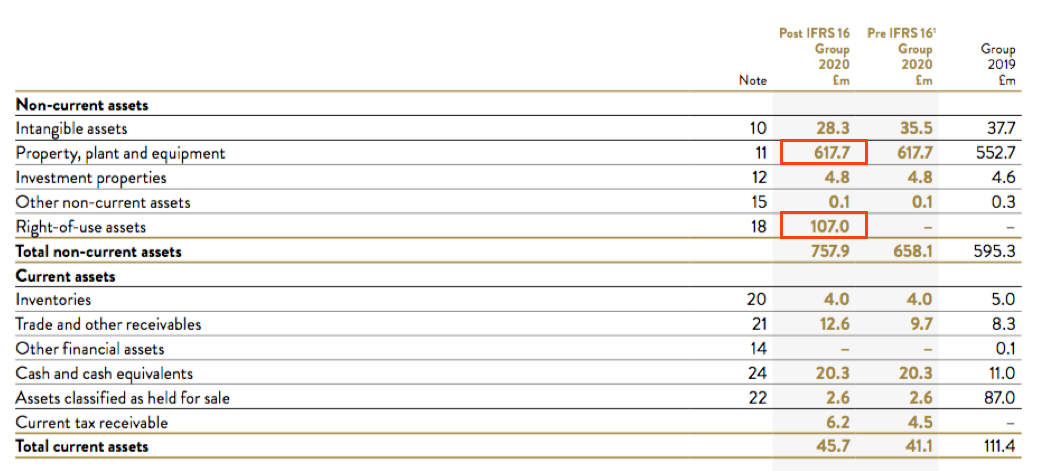

The tangibles of £725 million are in fact represented by a combination of property, plant and equipment, and right-of-use assets:

The right-of-use entry can be ignored as this is essentially an accounting concept that places a value on lease agreements.

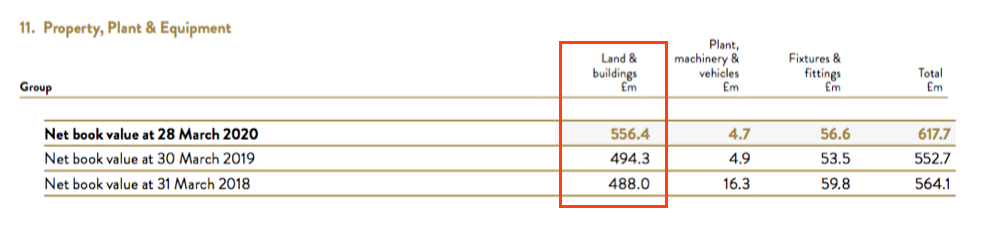

The real-world assets are contained within property, plant and equipment, which the annual report reveals to be mostly land and buildings:

Fuller’s says 91% of the £556 million land and buildings are represented by freehold properties:

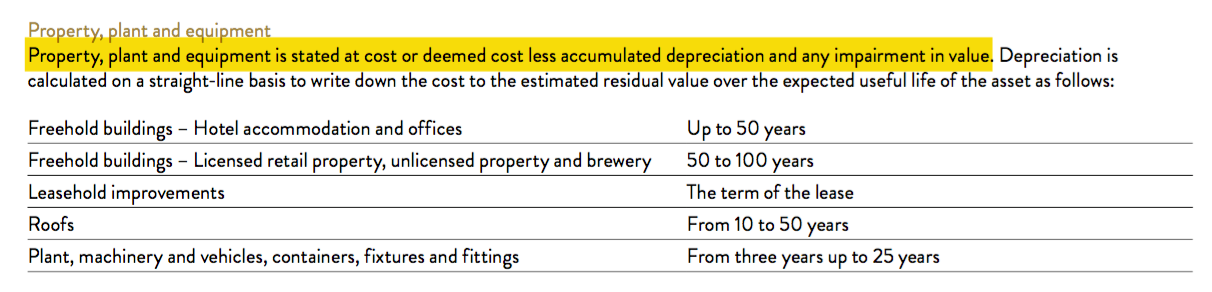

What’s more, the report small-print says the properties are held at cost (or an impaired value if lower):

This accounting policy is important because that £556 million book value may be significantly less than the true market value of the properties.

After all, Fuller’s has operated since 1845 and properties bought decades ago could be carried in the books for nothing and yet today might be worth millions.

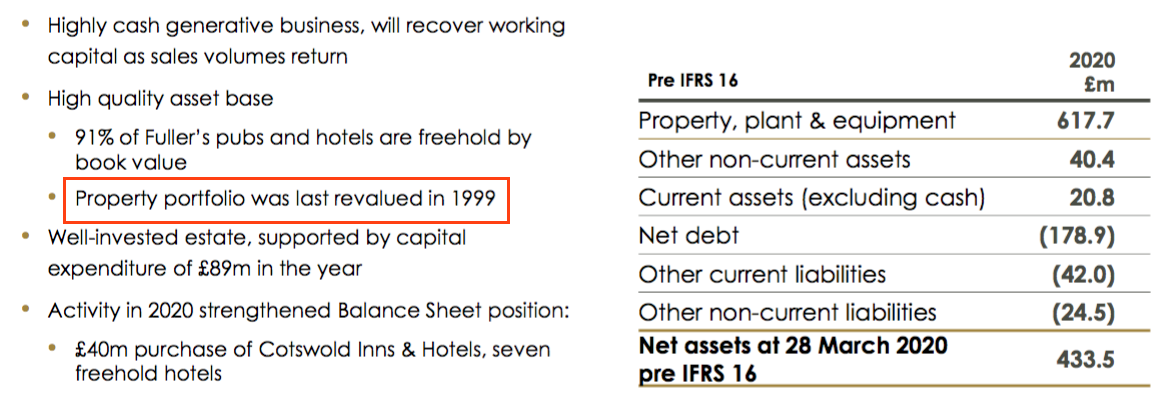

Further sleuthing leads to the 2020 results presentation:

Fair enough, 1999 is not 1845, but the powerpoint does confirm some properties are valued in the balance sheet at prices from 21 years ago.

One last point on the freeholds — the 2020 results reported:

“During the year we also sold two of our freehold pubs for £11.4 million, resulting in a profit of £9.6 million as disclosed in separately disclosed items.”

I very much doubt all of Fuller’s pubs can be sold for five times their book value, but pockets of inherent balance-sheet undervaluation must surely exist.

Borrowings and pension deficit

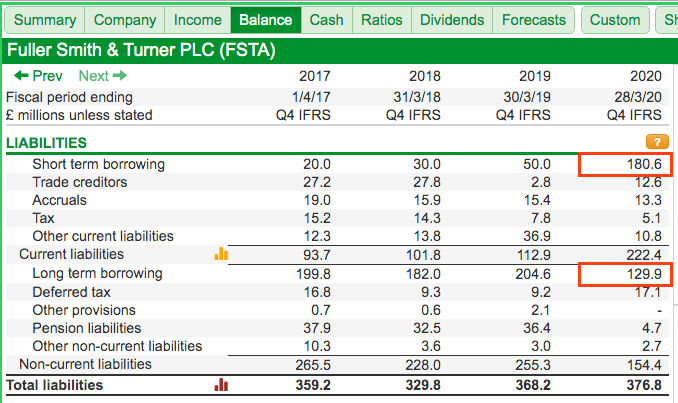

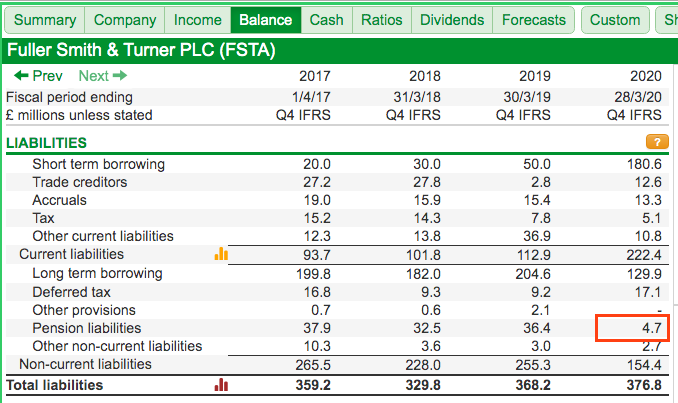

Now to Fuller’s liabilities. SharePad reveals the largest liability to be borrowings that total £311 million:

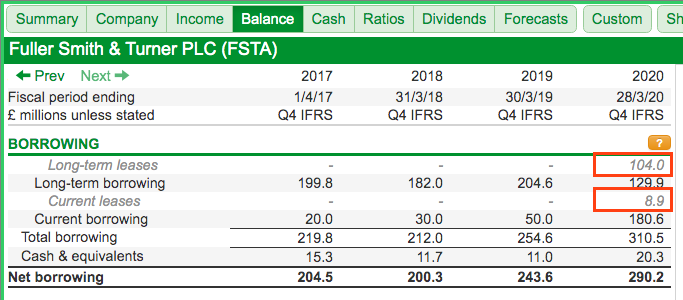

Borrowings include lease obligations, which total £113 million:

Conventional debt is therefore £198 million, and so the ‘loan-to-value’ ratio on the £556 million property estate at the March year-end was 36%. That level of gearing does not feel onerous to me.

Bear in mind that Fuller’s has said monthly lockdown cash burn was between £4 million and £5 million, so total debt may now be close to £220 million.

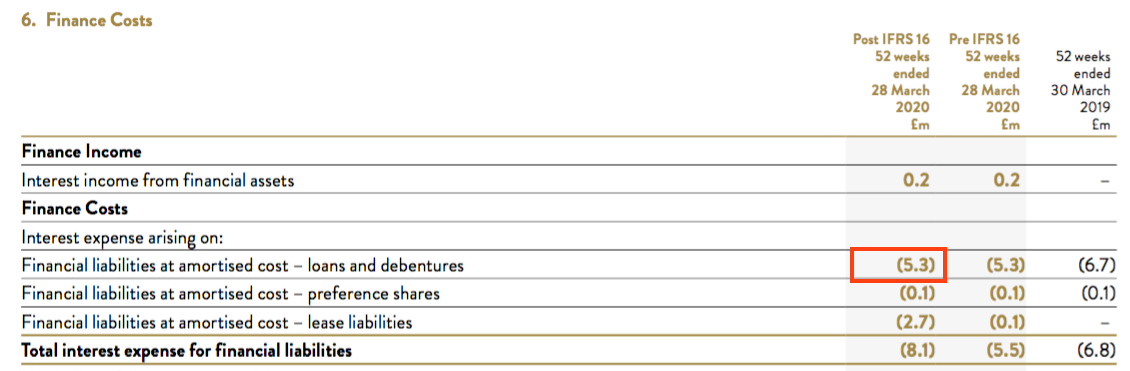

The annual report shows interest costs on the debt was £5 million:

Interest of £5 million on debt of £198 million gives a very reasonable rate of 2.5%, which suggests the lenders saw Fuller’s as a good risk before Covid-19.

Although Fuller’s latest results did admit “during the second half of the financial year, we will begin refinancing discussions with our lenders”, I am hopeful the discussions will be relatively straightforward.

Pub groups JD Wetherspoon, Young & Co, City Pubs and Revolution Bars have already tapped shareholders for extra support during the pandemic, and Fuller’s would surely have done likewise had its debts been troublesome.

Other liabilities include a pension deficit of £5 million:

This liability does not look problematic after Fuller’s made a special £24 million contribution to the scheme during 2019. Note that the £24 million was not charged to earnings and represented more than twice the cost of the 2019 dividend.

(The £24 million payment reminds me that pension deficits are often financial ‘black holes’ that continually absorb cash for no shareholder benefit!)

Forecasts and valuation

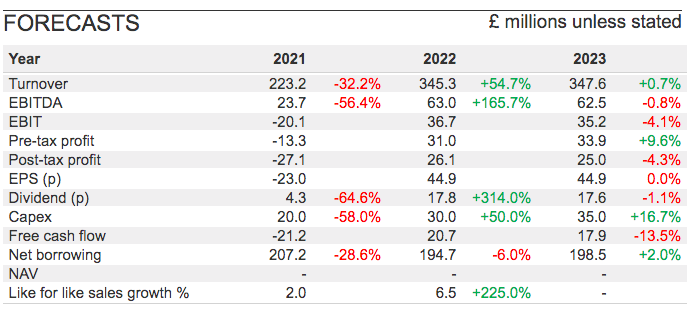

City brokers reckon trading may return to ‘normal’ for the year to March 2022:

July’s results seemed reasonably optimistic about post-lockdown trading:

“While it is too early to draw any meaningful conclusions, we are comfortable with the level of trade and we continue to monitor footfall in those areas where our pubs are not yet open.”

An AGM statement later this month could give further clues to any recovery.

I have to admit that Fuller’s £318 million market cap could in fact be justified. After all, the £556 million property estate less debt of perhaps £220 million does give £336 million.

That said, ignoring all those years when the shares traded well above book value seems very harsh to me. Fuller’s history suggests a profit revival will emerge at some point, and a complete recovery could even see the shares back at £12:

I might be wrong, but I sense Fuller’s freeholds should limit any further downside from here. The business does not seem burdened with the financial and structural troubles of Hammerson, but of course nobody really knows how the pandemic will play out.

At least Fuller’s chairman is confident. He has reminded investors about the firm’s extended history, which certainly put today’s uncertainties into perspective:

“Fuller’s celebrates 175 years this year. While it may not feel like a time for celebrations today, we have survived global recessions, world wars, the devastating Spanish Flu epidemic and all manner of unexpected events during our history. Fuller’s is a company with time on its side and our long-term vision has never been more relevant. Your Company is in a position of strength as we exit lockdown”

Until next time, I wish you safe and healthy investing with SharePad.

Maynard Paton

Disclosure: Maynard does not own shares in Fuller, Smith & Turner.